How is an image felt? Artist Sophie Calle takes this question almost literally in her latest show Behind the Curtain, on view at Perrotin New York.

Calle’s work impressed itself on me for its illustration of humanity’s faulty precondition: that the narratives we tell ourselves are both integral and destructive; we crave stasis (photography) even as we long to animate the static (text). In indulging both, we suffer the confusion between fact and fiction, knowing and feeling.

Calle’s work has also been focused on the fine line between explanation, justification, and narrativization–their respective relations to perception and memory. Her newest works on show at Perrotin (and previously at Musée Picasso Paris) are no different. The varying opacity between the “curtains” on display seems emblematic of this differentiation, an invitation to question the resulting experience of spectatorship at degrees of image/text interplay. This visuo-linguistic tension asks: to what degree is concealment necessary for narrative?

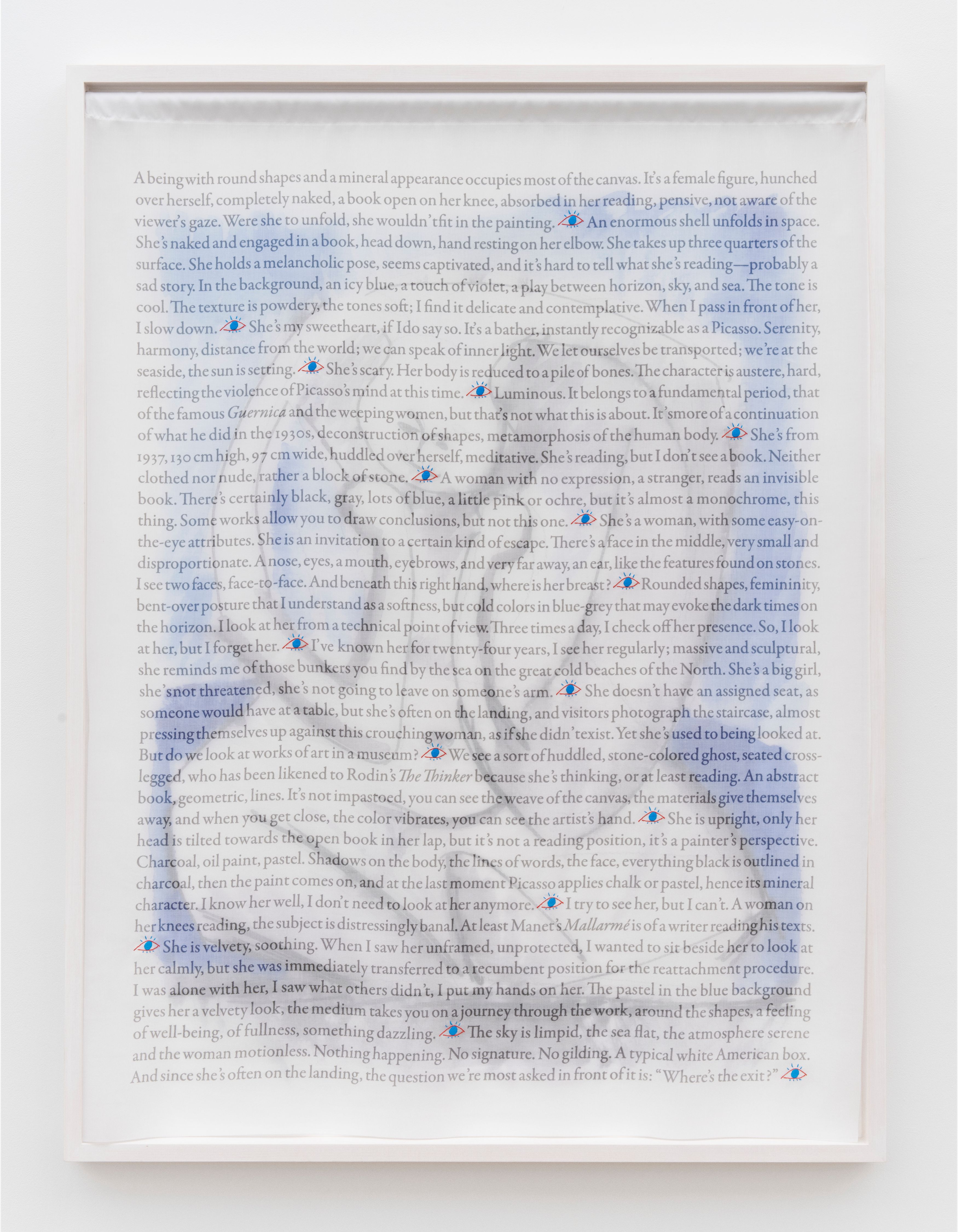

In Phantom Picassos, the viewer is instructed Please do not lift the curtain. One is left rather passive, standing detached from the sheerness of the veil bearing the explanatory descriptions, always spoken in the authoritative voice of fact: “A being with round shapes and a mineral appearance occupies most of the canvas. It’s a female figure, hunched over herself,” or “It is a little boy, I would say 3 or 4 years old, sitting at a wooden table.” Without the iconographic eyes between sentences, the viewer would struggle to find harmony between text and image.

“What we have is an oil painting but what I see is what’s going on behind it, the asphalt wall and the twenty or so hidden holes. It’s always the same: we unhook; we conceal; we make a new hole; we hang. Or I’m tracking the sun’s rays. The paintings, I hardly look at them,” reads the end of the veil covering Paul Drawing, 2023. This admission on the part of a Picasso Museum staff member points to a larger impulse: meaning is presumed hidden, therefore one’s attention is perhaps misdirected when there is no mediating layer between the object of beauty and our consumption of it.

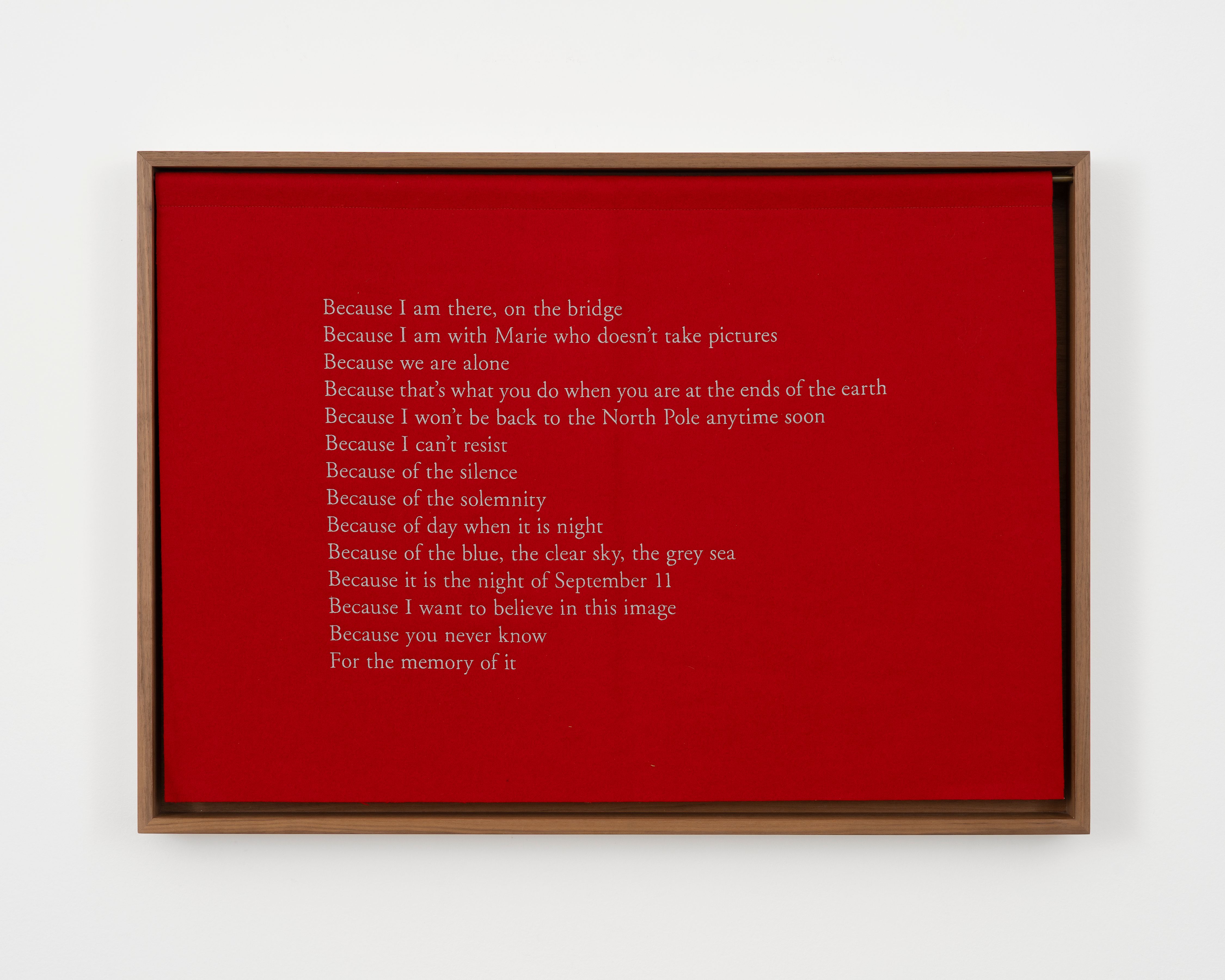

In Because, we turn from explanation to justification and, accordingly, are given permission to lift the weighty curtains. “Because I want to believe in this image//Because you never know//From the memory of it,” embroidered onto red wool that covers a large digital photograph of a melancholically blue body of water at twilight. In this series, since the viewer becomes the participant, required to lift the wool curtain to gain access to the image, the experience calls to mind the agency required to constructively narrativize, and accordingly mirrors the labor involved in creating and retaining a memory (often constructed by a simple, yet inscrutable impulse, “Because what else after nothing more?”, and sustained by our labored revisiting of that effusive instant).

Since Calle is sparing with her language, the vignettes can be likened to an unshaded drawing. We as the viewer must complete the experience of her art with our own justifications, our own life stories. In this way, justification (as enforced by the repetition of Because, Because, Because…) is a highly generative endeavor. The higher the barrier for entry (the weight and opacity of the fabric) the more imaginative and active a viewer is forced to be.

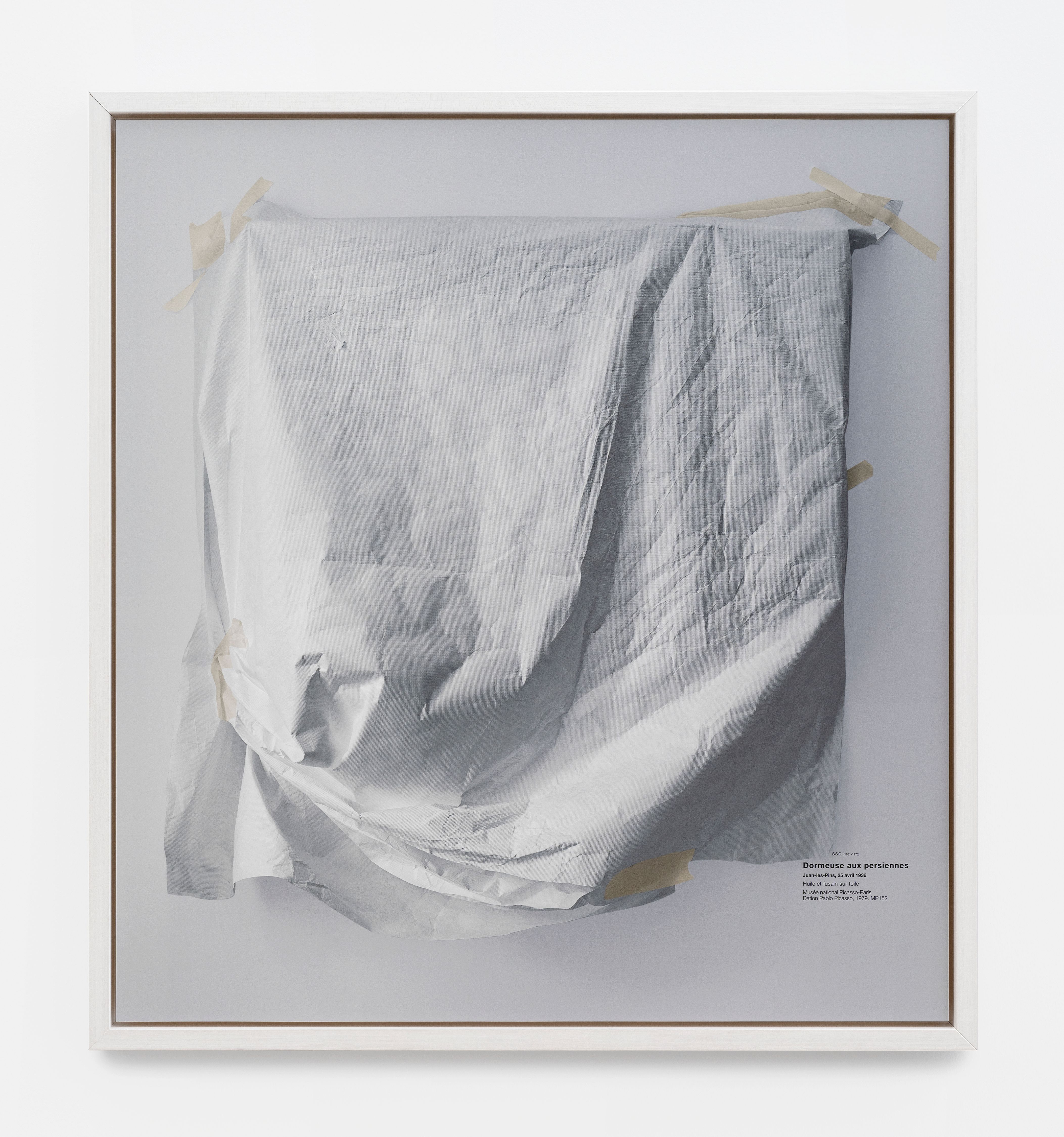

In some ways, Picassos in lockdown–the series of digital photographs showing the complete suppression of the iconoclastic paintings, completely hidden by shining paper covers, with only descriptive titles beside them–is the most evocative. Because the titles conjure the image, and Picasso himself is a monolith, we receive almost the most description from the least imagery. The imagination is tasked with doing all the work. Picasso is shelled of his spectral presence and reconstructed by the willpower of the viewer alone.

In his book on contemporary aesthetic theory, philosopher Byung Chul Han says, “only the rhythmic oscillation between presence and absence, veiling and unveiling, keeps the gaze awake. The erotic also depends on the staging of appearance-as-disappearance, on the ‘undulations of the imaginary.’” Sophie Calle’s work has always stood for this “rhythmic oscillation between presence and absence,” and is no better exemplified than in this latest collection of works.

Calle’s long-standing effort concedes that the narrative understanding of one’s life is, in many ways, a compensatory method of justification. We narrativize to justify what is simply gestural or instinctual, what draws us without effort. We seek justifications in order to sanctify what we’ve found, to convince ourselves and others that a true self, a true story exists.

—

Alternately described as a conceptual artist, photographer, video artist and even detective, Sophie Calle has been the subject of numerous exhibitions around the world since the late 70s. In her rituals, she blurs the boundaries between the intimate and the public, reality and fiction, art and life, while leaving room for chance.

Gemmarosa Ryan is a writer, photographer, and filmmaker based between New York City and Siena, Italy. Her work has previously been featured in Tidal Magazine and the New York Times.

.jpg)