“I don’t actually like talking about the film that much. Because that work already has writing in it anyway. It seems beside the point to say more,” Aristotelis Nikolas Mochloulis remarked in relation to his recent exhibition, I guess I’m not so special in the end, at the now permanently closed Hot Wheels London. But it would be a mistake to take Mochloulis’s apparent disavowal of authorial control at face value. Text and narrative shaped and sustained the exhibition, as they do his wider practice, which spans performance, publishing, moving image, and sculpture. Rather than a genuine retreat from authorship, we should treat the artist’s gesture of self-rejection as a red herring, a narrative device that clears space for his broader conception of biography as a vehicle. We might call this autofiction.

The work in question, The Baby & The Mouse (2025), is a video spliced together from DVD extras taken from Mochloulis’s favourite childhood films: An American Tail (1986) and Disney’s animated Hercules (1997). Shown on a television placed directly on the gallery floor, the footage is given a meta-narration by two stuffed toys (merchandise from the films) propped up by discarded training shoes and positioned as spectators of “their” stories. Voiced by Mochloulis himself, the plush mouse from An American Tail and a baby version of Hercules lament the absence of their owner, speaking instead to one another about anticipation, recognition, and the peculiar sensation of watching and hearing themselves unfold on screen. In addition to the dialogue, Mochloulis sings the songs featured in both films.

The Baby & The Mouse was one of three multimedia installations at Hot Wheels London. It was exhibited alongside How do you live? (1996-2003 & 2023), a series of 630 original C-print family photographs of Mochloulis taken by his mother before the age of seven, and Custody Reveal Party Balloons (2024), comprising five helium balloons papier-mâchéd with the real legal documents from his parent’s divorce. Together, the works articulate three distinct yet interconnected modes of working over, and physically processing, facts and memories from the artist's early childhood, handed down to him through official documents, private records, and nostalgic trinkets.

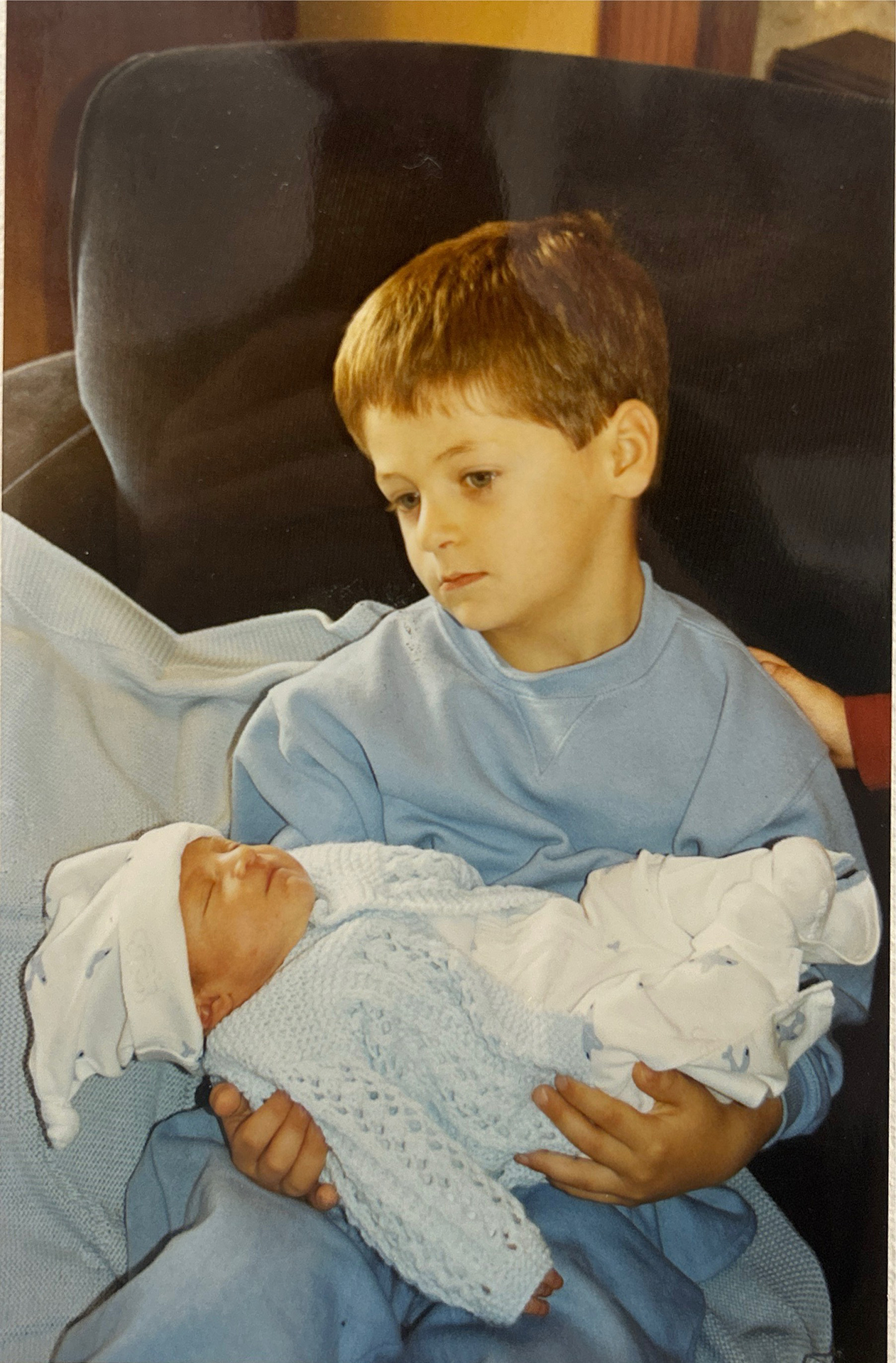

How do you live? dominated the front room of the gallery, installed in a dense horizontal frieze that wrapped around four walls in as close to chronological order as Mochloulis’s memory could manage. Each print is titled with the sort of phrase you might find handwritten on the back of a family photo, alongside a classifying serial number. The first photograph, 001. Birth, shows Mochloulis as a new baby yet to be cleaned up, and the last, 630. Blowing the candles at seventh birthday party, shows him at seven. In between are scenes of other birthdays, the arrival of siblings, Christmases, special occasions, trips to the zoo and playground, school plays, and other, less remarkable events. The series stops abruptly around the time digital cameras became commonplace and the 15 x 10 cm print ceased to be the standard for amateur photography.

Non-professional photography is often referred to as vernacular, meaning quotidian, handmade, or domestic. Yet cameras are an industrial technology, and even intimate, private photographs belong to a wider mechanism of value production. During the decades when analogue photography was the standard, film was purchased from monopoly companies such as Kodak and could be processed at home, though high-street photo shops developed as a secondary industry. Today, it isn’t even digital cameras that dominate the market, most people document their lives with smartphones, share images with family, friends, and strangers via large tech platforms that wield more power and money than many small nations.

In this material sense, photography always serves as a conduit between personal experience and wider political and economic structures, a condition Mochloulis acknowledged both in making his familial records private and in the acquisition structure of How do you live?, which can be purchased in one of two ways. Each print is individually for sale at the price of €100. Alternatively, the full set of 630 original prints is priced at €50,000. This is a high price point for a work by an emerging artist, and Mochloulis frames it as a speculative and performative element of the work. A collector assumes not only the responsibility of archival care for a substantial body of photographs, but also a gamble on the future career and potential market value of the artist, who is simultaneously the subject of the work.

The mutability and hollowness of retrospective valuation is a concern echoed in Custody Reveal Party Balloons. Physically empty, “full of hot air,” the balloons are covered in correspondence between Mochloulis’s parents’ divorce lawyers as they deliberated on the alimony settlement, an amount of money that is supposed to be equivalent to and substitute for the care that should be provided in a two-parent household. The communication is partially redacted, so even if the documents weren’t up on the ceiling they would be impossible to read in full. Yet despite the distance and acts of obfuscation, the papers are recognisable as the kinds of bureaucratic papers that document official and public life. Enclosed within them is the dissolution of a marriage, of a family, and of a home, the complicated and excessive experience of private life.

Held between the three works in the exhibition is a sustained play with figuration: abundant images of Mochloulis himself, his performed script placed in the “mouths” of stuffed characters, and the outline of a shared familial identity. Publicly calibrated, yet without confessional disclosure. What emerges instead is a tension between form and narrative as competing methods of making meaning from a life lived in Europe just before the full advent of digital technology and prior to the splitting of the home.

Biography here is neither origin nor explanation, but a material to be reorganised, deferred, and redistributed across objects, voices, and systems. The story we encounter of Hercules is not transmitted directly, but mediated through an Americanised children’s cartoon and then again through its DVD extras and tie-in merchandise. Mochloulis is Greek, yet in the 1990s even Greek children encountered their cultural inheritance refracted back to them as a digestible, synthetic American product.

If we do call Mochloulis’s project a form of autofiction, it is one that performs the genre’s relationship to mediation and technological circulation as well as its temporal instability. Read backwards from our present vantage point, Tao Lin’s Taipei appears to aestheticise the condition of the live-tweeted life. Read backwards, any divorce is inevitable, just as the commodification of once-sovereign cultures comes to seem unavoidable.

In the accompanying exhibition text for I guess I’m not so special in the end, Mochloulis recounts the dissolution of a childhood fantasy in three steps. Born in 1996, the same year the children’s television programme Teletubbies first aired, he recalls being told by his mother that he had played the giggling baby in the sun over Teletubbyland. He believed this until his late teens, when she informed him that it was untrue, and that he should stop telling people he had once been a famous baby. With the plasticity that characterises familial experience, Mochloulis adapted this un-truth into a personal mythology, understanding the lie itself as something intimate and precious. The text concludes, however, with a final annulment-cum-punchline: “Then last week I told a girl this story, and she said she knows plenty of people with this exact same story, plenty of moms that had lied. Ultimate prank on your own child, she said.”

Despite questioning the validity of self-exposition, Mochloulis framed his exhibition with a text that adopts the persuasive rhetoric of a tricolon. It leads the reader and viewer through the familiar stages of adult realisation: that none of us are, in the end, especially unique. He does so with performative flair and precise tragi-comic timing, allowing personal experiences and memories to resonate across his object forms, where they become shared, tangible, and spatialised. And despite Mochloulis’s self-confessed circumspection, it would be remiss not to give him the final line. As he has described personal memory, it is really just “choreographed imagery of something your mother said.”

—

Aristotelis Nikolas Mochloulis is the editor of Holdings, a former member of Incest School, and organises exhibitions in his apartment. Recently, his work has been included in shows at Artists Space, NYC (2025); Machine, Glasgow (2025); and Radio Athenes, Athens (2024). Earlier this year, he was in residence at Amant, Brooklyn, NYC in New York and at the Kunstverein Munich.

Alexandra Symons-Sutcliffe is an art historian, writer, and curator, currently completing a PhD on British documentary photography at Birkbeck, University of London.