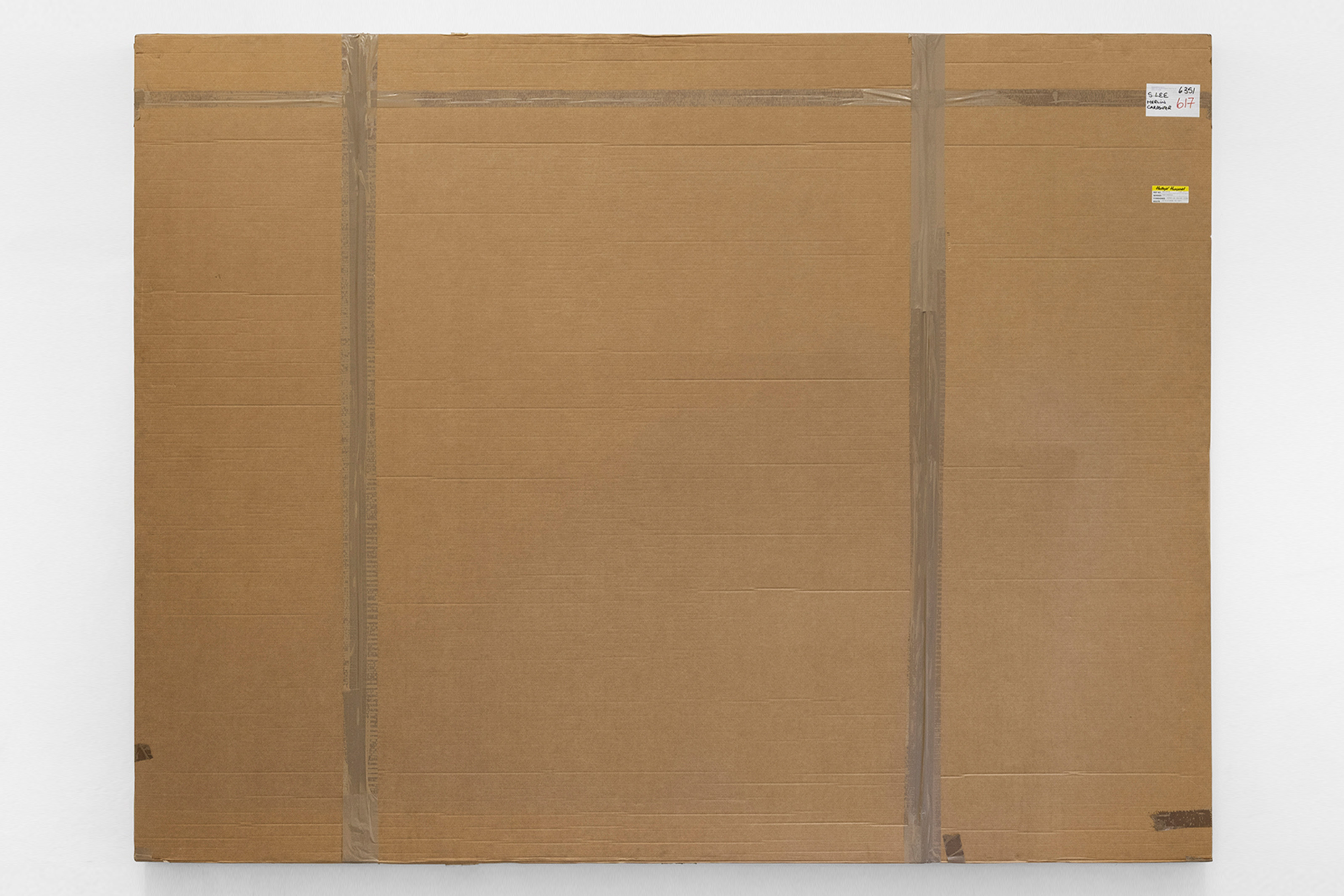

Merlin Carpenter’s exhibition at Diana consists of one work: a painting sealed in cardboard that will not be opened until 2081.

The painting inside — though we can’t see it — is one of a series of reinterpretations made by Carpenter of John Hoyland’s 1960s abstractions (unusually ambitious for British art at that time). Carpenter produced the copies in 2009 and formally requested permission to show them; Hoyland refused. He then sadly died in 2011. This made any display potentially actionable under copyright law until the end of a period lasting seventy years — 2081. The works were initially kept in Simon Lee Gallery’s storage, boxed in the same cardboard in which they are now shown. After many discussions, in 2017, for his third exhibition at Simon Lee, Carpenter exhibited the works exactly as they had been stored. They became monochromes of packaging, or metaphysical paintings of absence and impermanence.

The sales agreement Carpenter wrote for the series still applies for the work shown at Diana, and it carries with it a form of built-in violence: a trigger for concrete consequences at odds with the dreamy speculation that the work’s covered presence invites. If the cardboard comes off before 2081, even accidentally, “the Painting must be physically destroyed immediately without any record being made of this process.” The contract enforces the absence of the reproduced image through (the threat of) literal destruction: the meta-realm cannot be discovered, not even by mistake. By staying within the bounds set by these conditions, the works survive to circulate, but no matter where they go, they remain partly unseen.

The cardboard that wraps Carpenter’s paintings operates like a wall, but more softly. If stone walls have historically been built to provide necessary shelter and protection and also to exclude, cardboard could be said to perform similar operations, only on the metaphysical level and through weakness rather than strength. Cardboard excludes by being too fragile for someone to breach without them risking destroying what it protects.

Robin Evans once wrote that walls succeed not through what they are, but through what they prevent: the confusion of categories, the mixing of what should stay separate. Evans was obsessed with the moral and semiotic functions of walls, and how they organise retreat and exclusion as social and psychic operations.¹ In the case of Carpenter’s work, the cardboard offers the painting a small enclave while placing the viewer on the other side of a line that is as much legal as spatial. And it performs this double work only temporarily, with none of the permanence of the forms of exclusion enabled by stone, concrete blocks or perpetual storage. Its power is administrative, bureaucratic, procedural.

But cardboard is porous. Light works on it, and so too moisture, time, etc. Inside its shell, the painting itself is sealed away in polythene — a fact that testifies to the slow exchange between inside and outside that cardboard will inevitably allow. The painting’s visible outer wrapping thus falls far short of any strict ideal of containment. Carpenter’s conspicuous barrier actually admits almost everything, except sight: the one thing that art is usually expected to cater to.

The psychoanalyst André Green introduced the “dead mother” complex in the early 1980s.² This is a clinical condition in which someone experiences a once-loving figure “switching off” and becoming unavailable, almost inanimate, as if they have suddenly been reduced to “a cold core.” He was not talking about an actual corpse, but one’s relationship to this figure may still lead to what he calls “blank mourning,” a way of responding to a presence that is still there but offers no emotional engagement, a cold centre that blocks libidinal flow and energy. Carpenter’s cardboard is this as a surface. The barrier is thin, barely there — just corrugated paper, tape, shipping labels — yet it thickens in the mind’s eye into an absolute prohibition. Withdrawal (Hoyland’s? the estate’s? the law’s?) hardens into matter; what would normally remain invisible becomes visible protocol, a cold and emotionless rule about what can be seen and what must not be. In this context the “dead mother” is neither Hoyland nor Carpenter but instead the apparatus surrounding the work in which they are both implicated: the box, the contract, the gallery, and the estate, taken together. It’s this assembly of forms — material, legal, and institutional — that wears the face of refusal.

What is ultimately excluded by Carpenter’s cardboard is not a legal risk or an actual enemy but the viewer. And what is protected is not territory or an object but absence itself. The blank packaging accommodates a void where Hoyland’s painting both is and isn’t and where Carpenter’s copy sits in darkness, quietly accruing value.

When walls work, Evans argues, they make us forget what’s on the other side. This work insists we remember. Exclusion becomes content; maintenance becomes the work.

This is, perhaps, what institutions always do. They wrap shared culture in admin barriers, maintaining it through denial of access. The gallery that stores but doesn’t show. Always, there is some reciprocity promised, sometimes in good faith, if only as a message or gesture to a hypothetical encounter or the idea of posterity.

The work will outlast the current copyright terms, but won’t last forever. This isn’t a permanent wall, but something more modest. By 2081, perhaps no one will remember why it was wrapped, or what kind of art world it was wrapped out of. From where we stand now, it seems easiest to picture the future in broad strokes, as if it might be made of nothing but prophecies. Hoyland’s works already looked like vibrant hellscapes; catastrophe is accounted for. Harder to picture are the smaller-scale shocks that may be to come: a stray email from an old classmate, a local political win, the sound of music seventy years from now, ten years even. Prohibitions and artistic strategies might outlive their logics; a defensive wall may remain standing long after its war is forgotten.

Cardboard is more metaphysically complete than stone — or any abstract painting’s “dead mother.” It excludes over time and through expectations of care rather than in space. This allows transfer: the burden of maintaining absence moves from artist to institution, to whoever holds this wrapped thing, this wall made of almost nothing that screens a void, like the gold glass of an astronaut’s visor, an electric fence before a colourfield.

Gianmaria Andreetta

––

¹ Robin Evans, “The Rights of Retreat and the Rites of Exclusion,” AA Files 3 (1983).

² André Green, “Le complexe de la mère morte” (1983), in La folie privée (On Private Madness, published in English in 1986). He describes the child’s internalisation of a withdrawn mother. The object is neither fully lost nor fully alive. It is this idea of a withdrawn and organised absence that echoes here.