I’m moved to make paintings from images that I find have an interesting composition. Sometimes that means I know I will be making a painting before I snap a photo, but more often than not, I just find a good photo in the hundreds of photos I take all the time.

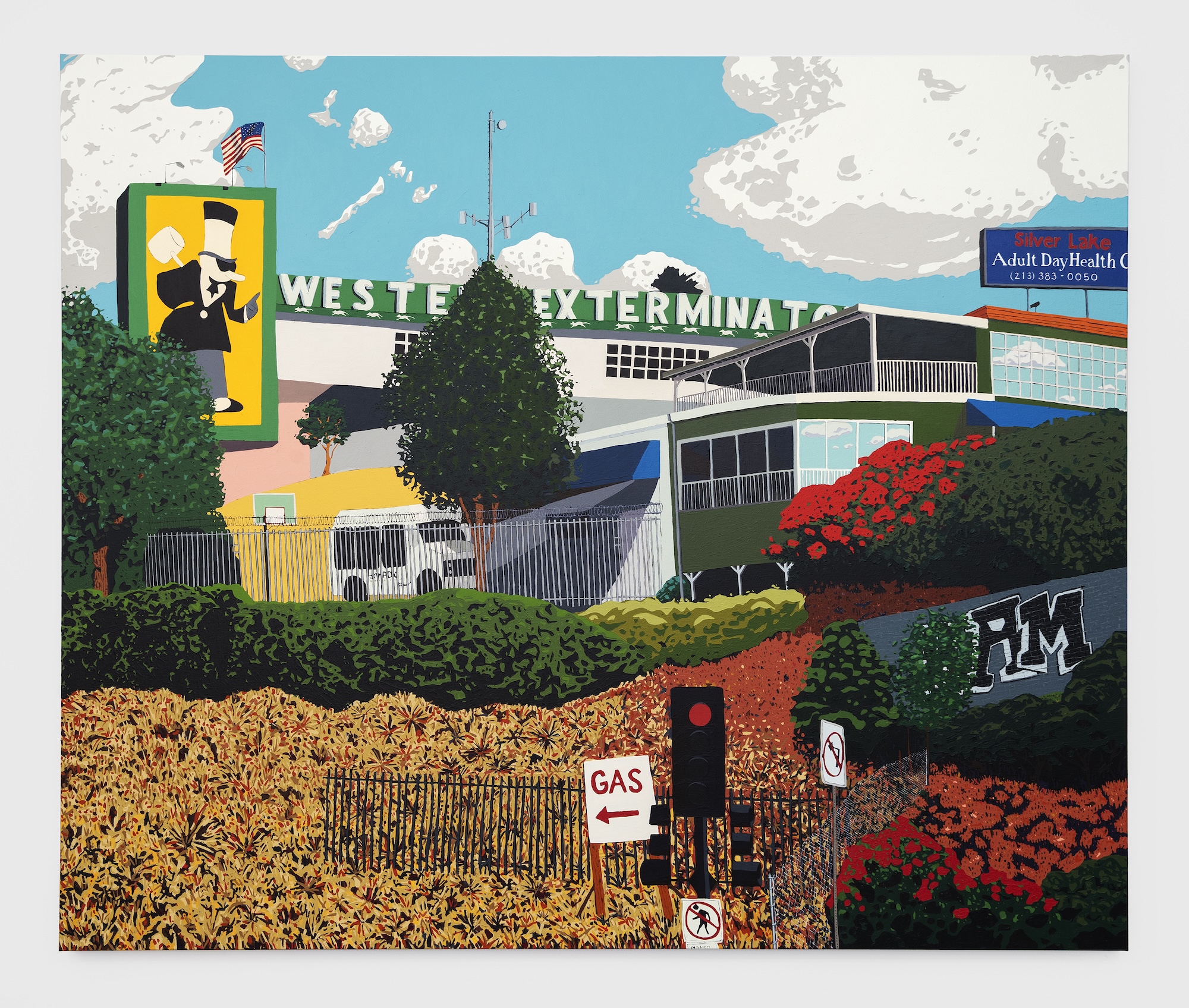

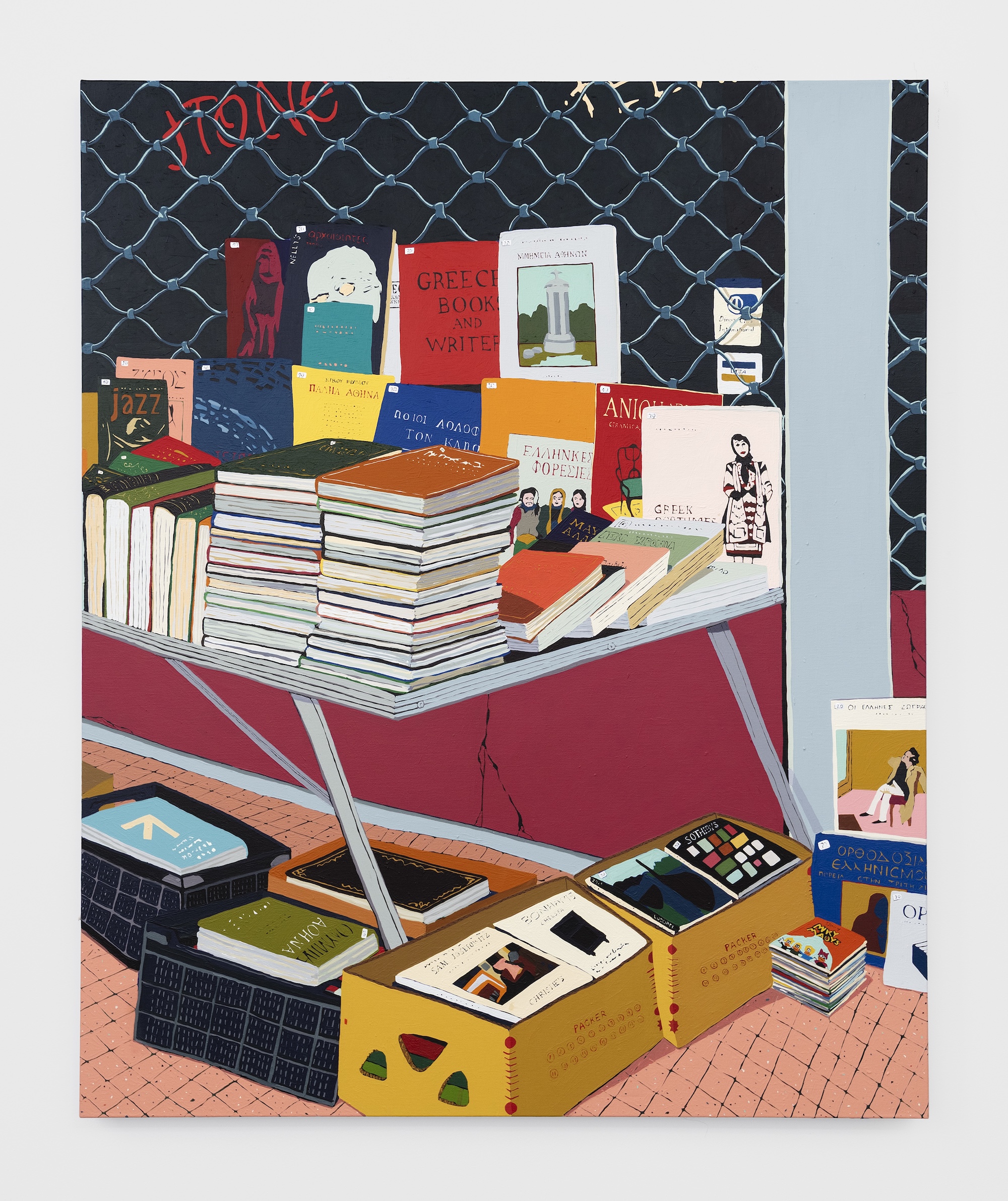

Well, I do enjoy slowing down to look and really examine a place, a thing, and the way they all connect. That said, I also really love a busy painting with plenty of visual fodder for the eye to take in. I usually try to get the viewer's eyes to move around either by lines that connect or colours that triangulate over the composition.

I think that choosing to be a painter today in general is an act of subversion, because you’re asking a viewer to look at something for more than 3 seconds. There’s little guarantee that anyone will enjoy what the artist produces, but the drive is there regardless.

Like any endurance sport, making an exhibition is a long game. It takes months - sometimes years - to bring a body of work together, and really, it’s the decades before that that form the foundation. That accumulated time, experience, and practice build the base on which everything else rests. A show doesn’t just come together all at once; it’s often something I’ve been thinking about or shaping in my head years in advance, and then slowly chipping away at in the studio.

There are phases - just like in any endurance activity - where you're building, pushing, and testing your limits, and others where you need to pause, reassess, or recover. That rhythm is really important. To sustain the work and keep it evolving, I have to give myself space not just to produce, but to take risks and make mistakes - because that’s often where the breakthroughs happen. So the endurance aspect isn’t just physical, it’s also about patience, resilience, and trusting that slow progress over time will lead to something meaningful.

I don’t actually think about the absence of the figure because the essence of people is so strong. It’s rare that I paint a pristine landscape without evidence of humans. And more often than not, it’s a domestic space (both indoor and out) that depicts a clear picture of the people or person that inhabits the space. In other landscape paintings, there are, at the very least, trails, sidewalks, signs, and trash.

When I start a painting, I usually begin with a photograph, just to loosely map out the composition directly on the canvas. I use it as a guide to get the elements in place, but after that, I tend to put the photo aside and let memory take over. From there, it becomes more about capturing how the scene felt, rather than how it looked. I want the painting to hold the mood or energy of a place, rather than be a faithful reproduction of an image.

Colour is often where I take the most liberty - mountains shift into purples and pinks, skies turn bluish brown, and shadows become more exaggerated or distinct. I’ll heighten textures, push contrast, or adjust light in ways that probably wouldn’t show up in a photo, but feel closer to how I experienced it. I’m not interested in replicating the image - I’m more interested in painting the atmosphere, the emotion, the ‘vibe’ of a place as it lingers in my mind. So in that sense, I think memory and painting are always reshaping each other in real time.

Actually, often my favourite paintings are the ones which I made from photos that I sat on for years. Those are the ones that feel sweetest, because I probably felt that the image was going to be difficult to depict, or maybe it might be a failure for other reasons. So when it’s finished and it wasn’t a failure, it feels like a little bit of magic was bestowed.

But to answer your question, a couple of months ago, I had been making a painting for an art fair that I wasn’t happy with. In the middle of the night, I woke and remembered a recent photo I had taken. I decided to scrap the art fair painting, and decided to work double time to make a new painting with the photograph. I worked overtime to finish the painting, and I was absolutely delighted with the outcome. It was much better than the original painting.

Yes - I have become more efficient with my time. Even if that means using the recovery moments well. Taking the much-needed lunch hour or weekend. But perhaps that would have also changed with age? It’s easy to burn the candle at both ends when you’re younger, but at some point, the law of diminishing returns catches up, and the recharge and reset allow me to make better work.

I represent space with the shrinking of pattern size rather than the change of colour or the muting of colour as it moves farther back in space. This is an aesthetic choice since I also have chosen to rarely have colours blend from one to another on the surface of the canvas.

When I’m in the painting - especially in someone else’s space - I tend to stay very true to what’s actually there: the books, artworks, posters, and personal objects that make up their environment. So in that case, the references aren’t necessarily intentional nods, they’re simply part of what I see and choose to include. When I’m painting my own space, it’s much the same - I’m painting the books I’m reading, the art I live with, the images I’ve chosen to surround myself with. I love looking at art, and naturally that finds its way into the work. So yes, sometimes it’s a gesture of homage - especially when I get to paint an artwork I really admire - but it’s also just about being present with what’s in the room. There’s a quiet pleasure in letting those references live inside the frame, without needing to be too pointed or overthought.