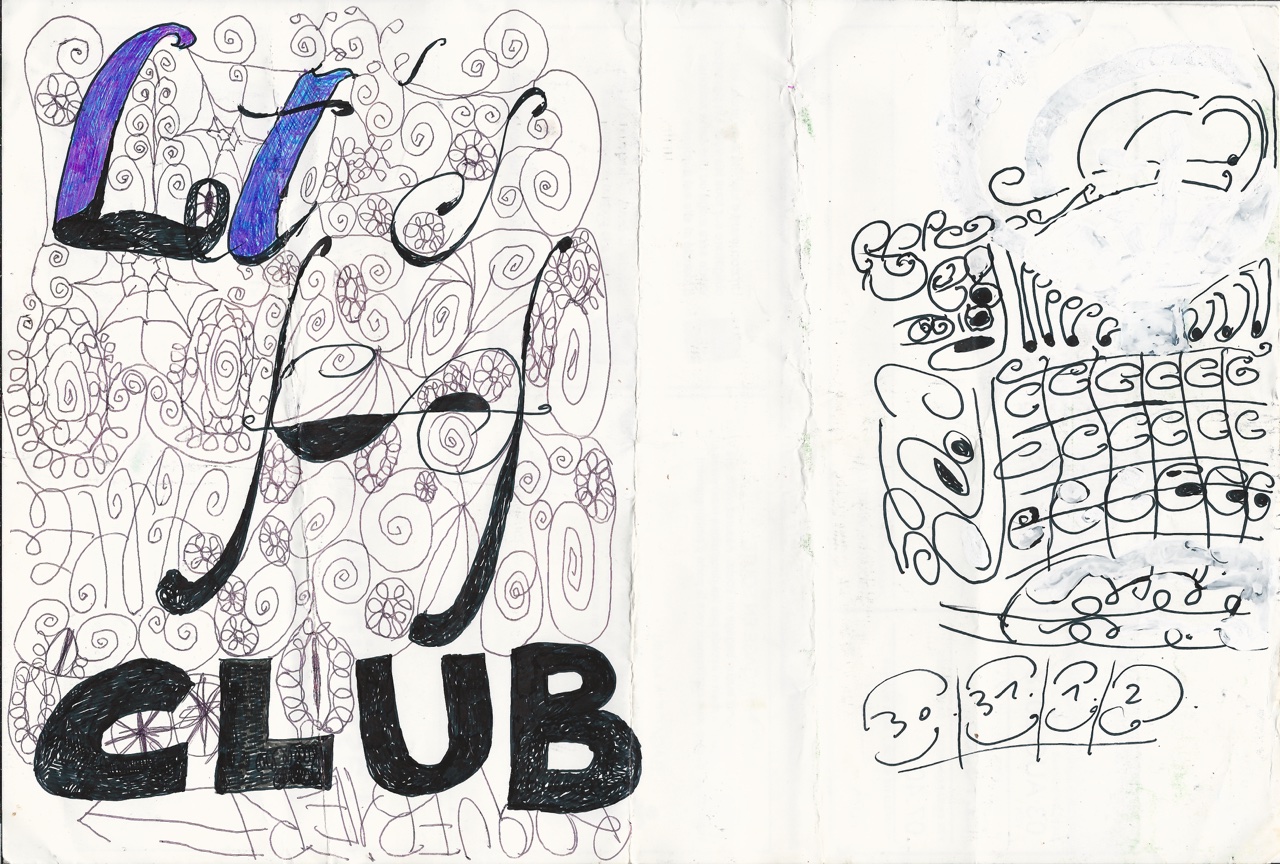

“The Door Bitch” (en français dans le texte!) was the nickname of a particularly nasty bouncer from ’90s Paris nightlife, some older friends often told us about. “Bouncer” doesn’t quite capture it; the French word physionomiste would actually be a better match. She had a drastic door policy and rejected almost everyone. She’s a figure among other imaginary bouncers I had in mind, among pictures of long, strange, and melancholic shoes and legs standing in line, suspended between desire and the expectation of being rejected, of not being stylish enough, conforming enough, or well-mannered enough. There’s a masochistic joy in waiting to be potentially refused. Those drawings suggest the party might be better outside the club and outside rejection, too. The inside is hors-champ.

H-Club was an almost-real club set up by my friend Jean-Luc Blanc in his parents’ garage when he was a teenager. He played records for the villagers who came dancing on Saturday nights. All the clubs in my work, whether real or fantasized, are mental spaces, empty boxes (une boîte de nuit) to be filled. It’s a box that channels desires, materials, and leftovers, and a place to think about music and the night, whether the sleepless night or the one when, deeply asleep, we dream.

I often draw sitting on my bed with my legs stretched out. In this position, my hand naturally traces half-curves that quickly, and almost involuntarily, transmute into high-heeled shoes. The wrist and hand interlace curves and stems. They appear just like flowers. I also adore the idea of high-heeled shoes, impractical and extravagant, so as not to touch the world too closely, or to touch it only fictionally.

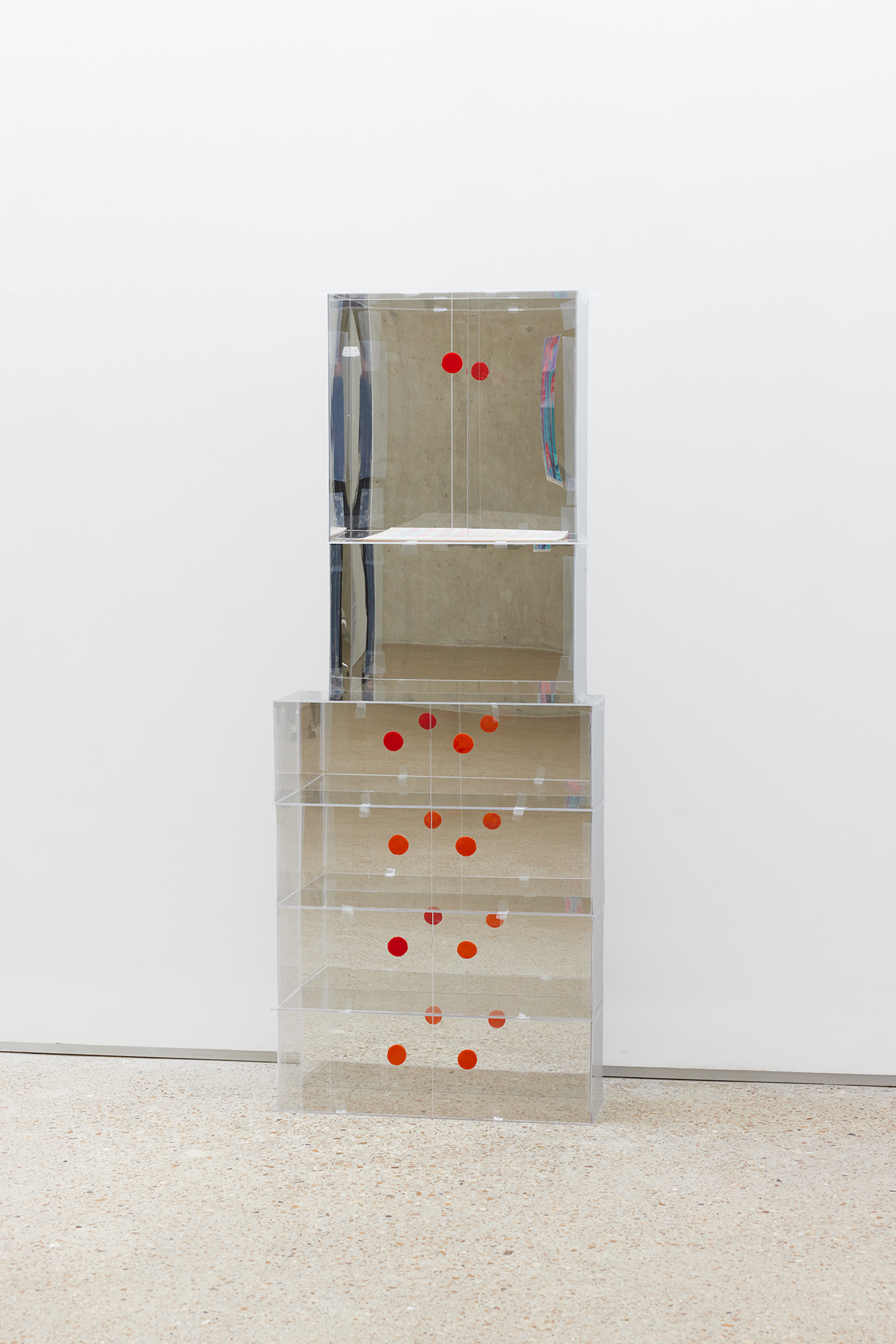

Dissociation opens with precarious shelves of plexiglas and tape that display a series of potential costume sleeves I made on my loom. In the following room, as though through a mirror, are drawings of long pointed shoes and slender flowers, like dissociated parts of the same catalog of fantasies—strange clothes, patterns to be worn in spirit, the mental possibility of an art tried on rather than looked at. The suit sleeves and shoes, stereotypical and fetishizable, are objects of power and vanity; in other words, of melancholy, which is undoubtedly the sensation I most desire to bring forth in what I do.

It’s not entirely clear, but it’s often the state I want to put myself (and us) in, what I want the thing I’ve made to do to me. It’s a kind of transaction: I want it to put us in a state of melancholy, since we’re made of things just as much as we make them.

It makes me think of Jutta Koether, who writes “The things that make art and the things that art makes” in her book f (1987). About those paintings, she says: “I’m everything they affect in me.”

When you asked me this question, I immediately thought of Sketch for Summer by The Durutti Column. That track lends its title to my piece (three of the displays in the show Dissociation), as a kind of dedication. It’s a scent I wanted them to wear. Listening to this cult track brings a kind of elation, but hollow, like dopamine for the void, or in a void, in an absence. That’s its melancholic effect. The melody breaks like waves against the echo of the guitar pedal and the drum beat, as if the echoes of sound arrived before the sound itself, from the future back into the past. But it’s not really something you can describe in words. It's something only music can do.

Again, Jutta Koether in f: “Music breaks open without you really knowing what it opens up. That’s why musicians say, in one form or another, that it has to do with feelings, a fffeeeeling, intensity and fun (…)”

I like to use the term mentalité (“character” or “sensibility” in English), far more supple than “conceptual.” Mentality can be an idea’s scent, its mood, its style. In my work, the character of things is unstable, indefinite, affected and affecting, bound up with feelings and lived yet diffuse memories. This phrase by artist Martine Aballéa is stuck in my head like a mantra: J’aime les choses qui existent plus ou moins. (I like things that exist more or less).

In Dissociation, abstract patterns of woven grids and strips are everywhere, each one a small possibility of infinity. Like an equation, patterned sleeves stacked one above the other are displayed on what looks like store shelves. A photocopied hand sticking out, or a red wool snake’s tongue, is the only clue telling us we’re looking at costume sleeves or possible snakes, and not purely abstract forms. Because of this, they become figurative, though it all remains uncertain. We’re right on the threshold of that duplicity. It’s like I always want to get back outside, to play pretend beyond the symbolic world of art exhibitions.

I’ll tell you about a piece: Stairways to Go Down Down Down at MAMC+ is a model of a staircase leading down to a basement club, surrounded by mirrored walls that reflect ad infinitum. It’s the size of a small transparent Plexiglas piece of furniture. The idea of descending those stairs immediately makes me hear Brian Eno singing, “falling down down down, ever falling down.” You go down into that dark red velvet pattern with that beautiful chorus playing as you descend into the club. As is often the case in my work, there’s a kind of semi-conscious word association between the title, some music, and what you’re seeing, things added together that might create meaning through superimposition. The carpet pattern looks as much like a leopard’s back as a river of blood seen under a microscope. The magic of pattern is its ability to be several things at once, at different scales and worlds. You see this in natural forms: pebbles and water in a riverbed, blood inside a vein, a leopard’s coat, clouds in the sky. This human urge to cover every surface with a pattern fascinates me.

I love the three artists you mentioned, especially Amelie von Wulffen’s autobiographical comics. Keren Cytter’s diaries have also stayed with me. I like thinking about Agnes Martin from a distance. I love her, and I love stealing from her, turning her work into a fabric pattern. I started weaving on my loom with very fine thread, making striped patterns, drawing from one of her watercolors composed of three yellows that repeat one another.

With Marni, it’s the same thing. It was a runway show I saw online, kind of by accident. 2023 was a very yellow season, and that yellow really struck me, how fun and provocative it felt. I wanted to remake those outfits after seeing them on my computer simply because I loved them. Make them because I can, so I can have them. It’s a way of reclaiming the symbolic power of these things by fabricating a state of possession through vampirizing cultural objects (because I love them), and also my friends (because I love them too).

My loved ones live at the very core of the work. Part of my work is literally to reproduce and suck on preexisting forms, recreating dupes or lo-fi objects. Those objects often belong to my friends, like Charlotte’s skirt, or Philip’s xoxo comforter. I distance myself from those close relations when I involve Agnes Martin or other canonical references, but they all end up together in the work. There are a lot of fictional characters, too. It’s anti-speciesist.

I did this piece called The Party at Barnett’s in 2013. It was a series of more or less abstract or architectural drawings hung all together on a big wall with no space between them. You couldn’t really tell from reading their titles who Barnett was, whether it was a reference to Barnett Newman and a possible party that might have happened in the 1980s in his studio in the L.A. hills (in my head, I thought Barnett Newman had lived and worked in Los Angeles rather than New York), or Barney from The Simpsons, a character whose pathos really moves me. The drawing titles existed in this kind of speculative projection between the two characters, an American loop from Barnett to Barney. The pieces and their titles are often naively relational, a way of passing along references, stuff I really love, secret dedications to people or things, as if I were working for a fictional community that brings together all my loves.

I work in my apartment in Saint-Denis. I wake up and get up. I work; I move from one activity to another with no set plan. I don’t have a fixed structure. Since my process is genuinely very slow, everything stretches out with no end in sight. My work is made of digressions and micro-events that pull me away from what I’m doing: appointments, whims, and all the stuff outside (I work at an art school). Sometimes people have this preconception about my work that it’s supposedly “meditative.” But I’m the opposite. I’m anti-meditative! If I do what I do, which is immerse myself in hyper-repetitive gestures like weaving, embroidery, or the drawing I do, it’s precisely because it lets me think about everything else at the same time, like a claustrophobic person who absolutely needs parallel lives running in dual tracks. When I work, I listen to music, podcasts, I call friends, I watch way too much trash TV, bad enough that I don’t mind only hearing it, since my eyes are glued to what I’m doing.

In winter I usually draw in my bed rather than anywhere else, and the hotter it gets the more I move toward the living room, where I weave and stage things around me. Colors have their seasons too, like in fashion. I’m in my yellow season right now.

The pieces have their routines, familiar paths that infinitely repeat. Patterns, motifs, and symbols keep showing up—a continual variation tied to the social spaces of the city’s nightlife. I’m not sure why, except that it’s intrinsically linked to the music I love and listen to while I work. Western pop culture triggers immediate melancholy in me. Stripes like black and white piano keys, electronic music, repetitive, new wave, cold wave playing in the background (and in my work), cigarettes, bottles, 1980s cocktail glasses, stiletto heels, flowers, empty storefronts, one-dollar bills, dice, watches and clockmakers, empty boutiques, lots of mirrors, notes. They’re status symbols that are kind of stereotypical and superficial: what is consumed and what consumes itself.

I'm working on a duo show with Benjamin Seror that will open on October 31, 2025, at Archivio Gribaudo in Turin, curated by Lilou Vidal.

Two things immediately come to mind: Paulina Peavy’s exhibition, which I saw at Emmanuelle Campoli in Paris in July which was incredibly beautiful, and a really powerful poem by L. Etchard, a Uruguayan poet who writes in French, a poem I find untranslatable into English, that I read in the journal Traverse, published by the Fondation Ricard. I can’t get it out of my head. I’m going to learn it by heart.