A couple of years ago, Ned curated a show at Public Access with the same name. He reached out after seeing a photo of me in Texte Zur Kunst, where I was making clay reliefs on the facade of the Brooklyn Public Library. He said, ‘This image tripped me out because it looks how I look when I'm tagging, but it’s not.’ It was cool hearing his perspective. I don’t typically discuss my work in the context of contemporary graffiti because I don’t have a tag. Still, the considerations surrounding time, language building, and navigating public space are similar.

In early conversations with Ned and Leonie, we discussed authorship and the concept of re-authoring—how tagging a building is one form of authorship. Meanwhile, as I pull fragments of civic language and reconstruct them into my poems, it is a different form of re-authoring. The works in the show, which date back to 2021 and 2023, were developed through collaboration. I shadowed a monument technician and pressed clay into the letters that would typically be covered by graffiti, extracting words or language from the site.

Those language-based works aren’t in the Museion show, but I have a whole matrix of fonts from buildings across the city. I think the early work was attempting to contend with the failure of language through these sites, and in a sense, breaking down symbols. As I continued to develop this method, I became increasingly interested in pushing the choreography of building sentences through urban space and holding letters in my hand. If I needed an extra ‘R’, I would have to take the train back to the site, press clay into the surface, and delicately carry this letter back so it wouldn’t get squished. Each word became very precious in this way. I liked the idea of hitting myself against a word to generate a form of handwriting or poetry.

Much of my methodology was developed by exploring how to make a mark without leaving a trace. It’s both a technical challenge and a conceptual question. Mold-making and clay pressing became ways for me to navigate working within public space—loopholes, in a sense. I’m interested in collapsing or flipping tools that emerge from different, even ‘opposing’, fields. Some of it came out of lessons learned through wheatpasting. Recently, I adapted this obsolete archaeological technique used to study language—‘epigraphic squeezing’—into a casting technique. My friend Camila Palomino and I collaborated on a psychogeography-style workshop with Dia, allowing participants to create spatial records using paper. There was a man in Athens who used to make brushes that were crucial to this technique for every academic, but he had passed away and didn’t have an apprentice. So I spent six weeks cold-calling archaeologists to try to translate the formula for rougher cement surfaces. It’s also essential for me to think about material strategies that are lightweight and easy to carry.

I’m always looking for moments of a kind of public intimacy. Things disappear, reappear, or change quickly in the city. A wheat-pasted work disappears almost immediately; it goes up to get covered. It’s probably the fastest you’ll see something disappear and reappear in public space. The more I work, the more I realize I’m trying to set up conditions for a chance to emerge and guide me, whether it’s a conversation, an encounter in the city, whatever. One of my ceramic text works, I AM TURNING INTO AN ANGEL PLEASE LEAVE, came from something a woman said to me at eleven PM while I was making reliefs of letters at Grand Army Plaza in Brooklyn.

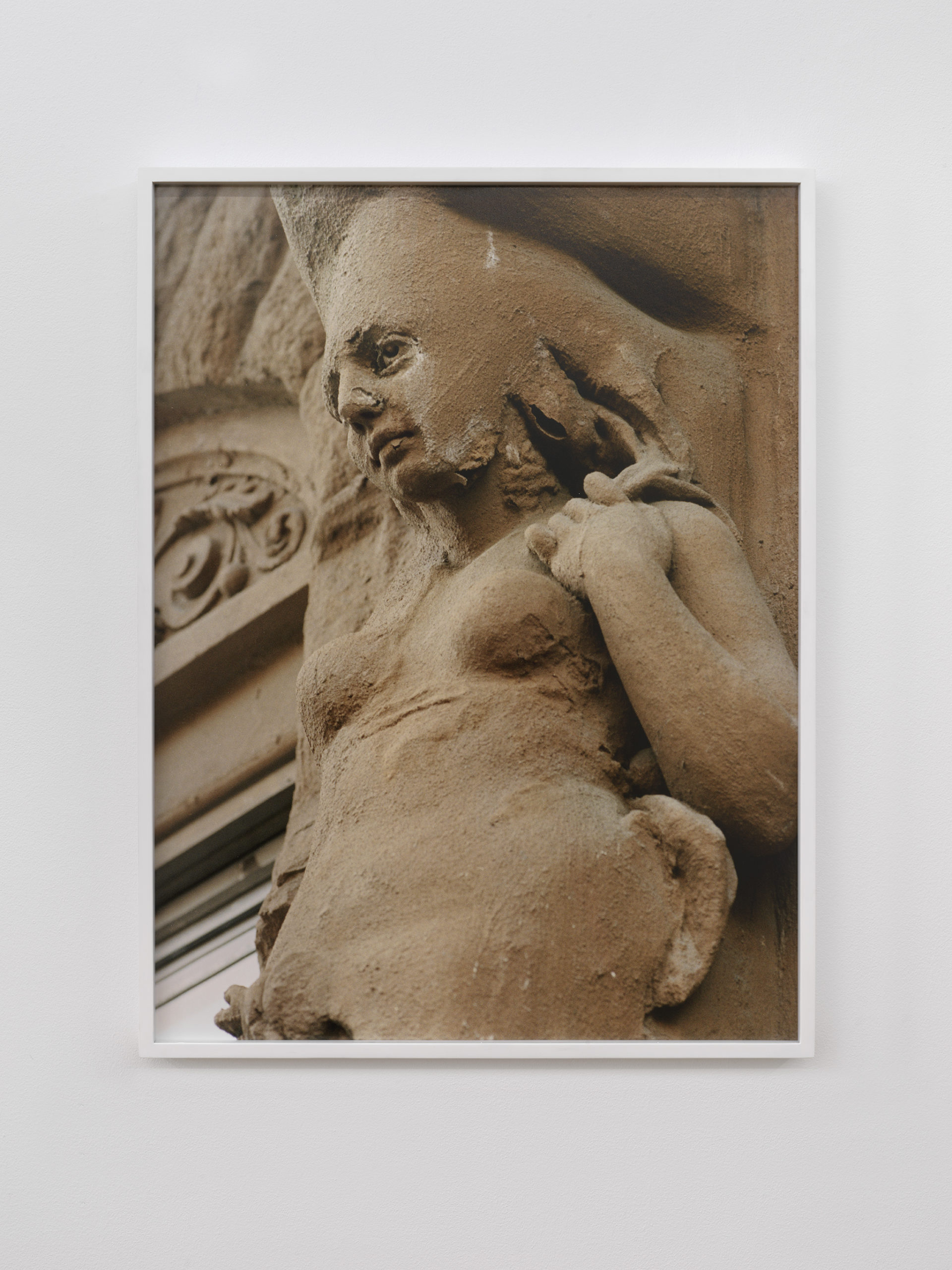

The Museion exhibition has two works. One is from my second solo show, a ceramic cast of a manhole, and the other is from my first solo show, Veils. Those are latex pulls of window frames, a process similar to Heidi Bucher’s latex skins (skinnings). I became obsessed with a statue on St. Mark's and these highly ornamental buildings around East Village/LES. I would pass her eroded body on my way to the train, and her face just looked like she had seen it all. I later noticed the same statue on Henry Street. I took photos and checked back months later, but she was no longer there. The disappearance struck me and ultimately pushed the project forward. It reminded me that everything I was looking at wasn’t permanent. I was lucky to find a musician who connected me with the super of the building on St. Mark's, who permitted me to make the mold. For all those works, I’d find someone willing to let me onto the fire escapes—fire escapes were essential to the process because they’re these kinds of thresholds between public and private.

Exactly. For a brief time, I became a part of someone’s routine. When I work on fire escapes, it feels more private and almost voyeuristic because I’m just hovering at the edge of someone’s life for a few days. This one person had asked me to feed her cat. When I create a mold of a doorway, I find that many curious people wander in and out, sharing their stories. It turns into a chance to tap into the lived histories and experiences tied to that space, creating all sorts of unexpected interactions with passersby. My most recent project was maybe the most ‘durational’. I spent 5 days making molds in this motorcycle garage in Pennsylvania. My practice flows with and through people, where I’m a kind of transient and active guest.

There’s an essential layer of ornamentation history in the context of that show and the ‘veil works’. I was examining how ornamentation is used as a visual signal in public spaces within tenement buildings in the early 20th century. Many of the decorative tenement facades were built by first- or second-generation immigrant contractors and became vilified by early 20th-century urban reformers as ‘veiling’ illicit activities. These parallel dialogues today revolve around the kind of glass box developments, what’s ‘cleaner’ or ‘safer’, and more ‘elevated’.

I moved around a lot as a kid, so my relationship to place was a bit strange and fragmented. Maybe also why I gravitate towards places that hold a context or history that isn’t obvious on the surface. I used to understand my work as engaging with memory as a site or distinct subject. What I’ve realized is that my process is just as much about collecting memories as it is about creating them. People see the work as referencing ruins as a canon, which, of course, is there, but they are also direct remnants of a series of encounters.

I don’t fully fit into the research-based category, nor do I fully fit into the street art category. Research is a big part of my practice, but I’m not trying to de-materialize the work. I’m still making objects and trying to create an encounter that mimics how I felt while engaging with the sites.

Yes. For instance, the manhole works—though it seems obvious, it represents another kind of threshold between internal and external for me. There’s an artist, Sari Dienes, who I think would’ve fit perfectly in this show. She created amazing rubbings of sidewalks in the 1950s and 1960s and was a kind of blueprint for Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, and others. Her work situates abstraction and gesture directly in sites of foot traffic, which interests me more than either of them. Heidi Bucher also influenced my latex works. I also think about Colette, whose work with crossing signs and street performances is amazing. She’s also in the Museion show. I met her in 2020, and I admire how she’s navigated public and non-canonical spaces. As for language, after completing my first body of work, I began to explore concrete poetry and the work of NH Pritchard.

Yeah, and there are so many influences, both contemporary and historical. The entire process is collaborative, involving artists, neighbors, strangers, researchers, and even conservators who help me create the work.