Donned in a long Betty Boop T-shirt, lips rouged with shadowy eye makeup, Elizabeth Englander reclines in the promo image for her solo exhibition at a. SQUIRE, The Elizabethan Lumber Room. The scene would be kitsch, but the artist's glare corrals disquiet. Englander’s character knows we are looking at her, casting associations, and in turn gazes right back at us, challenging our inscriptions. Blurring the personas of femme fatale and allegorical Venus–Aphrodite, cam-girl, nude from an early modern painting–Englander here personifies the porosity of iconography: how an icon’s meaning shifts across places and times, becoming legible in relation to social worlds and their histories.

Englander has long been interested in such shifts; particularly in symbolic figures that recur across cultures. When the photo was taken (2010), Englander was exploring the malformation of the cartoon character Betty Boop, with her self image pastiching Boop’s transition from an audacious moniker of liberation to a signifier of sell-out femininity. In performing this critique of social transformation, however, Englander was left feeling what she describes as “the contingency of [her] sense of self”–a recognition that selfhood is a precarious amalgam of social, cultural, and temporal perceptions, vulnerable to ideological change in much the same way as Boop.

The pose seen in Englander’s portrait recurs throughout The Elizabethan Lumber Room, in each of the ragtag statuettes that dot the exhibition space. Materially diverse and rugged, these forms are not the personifications of an artistic past; instead, resting upon antique bookcases–the kind favoured by barristers–they expose how a selfhood is made and malformed through strange sociocultural affinities.

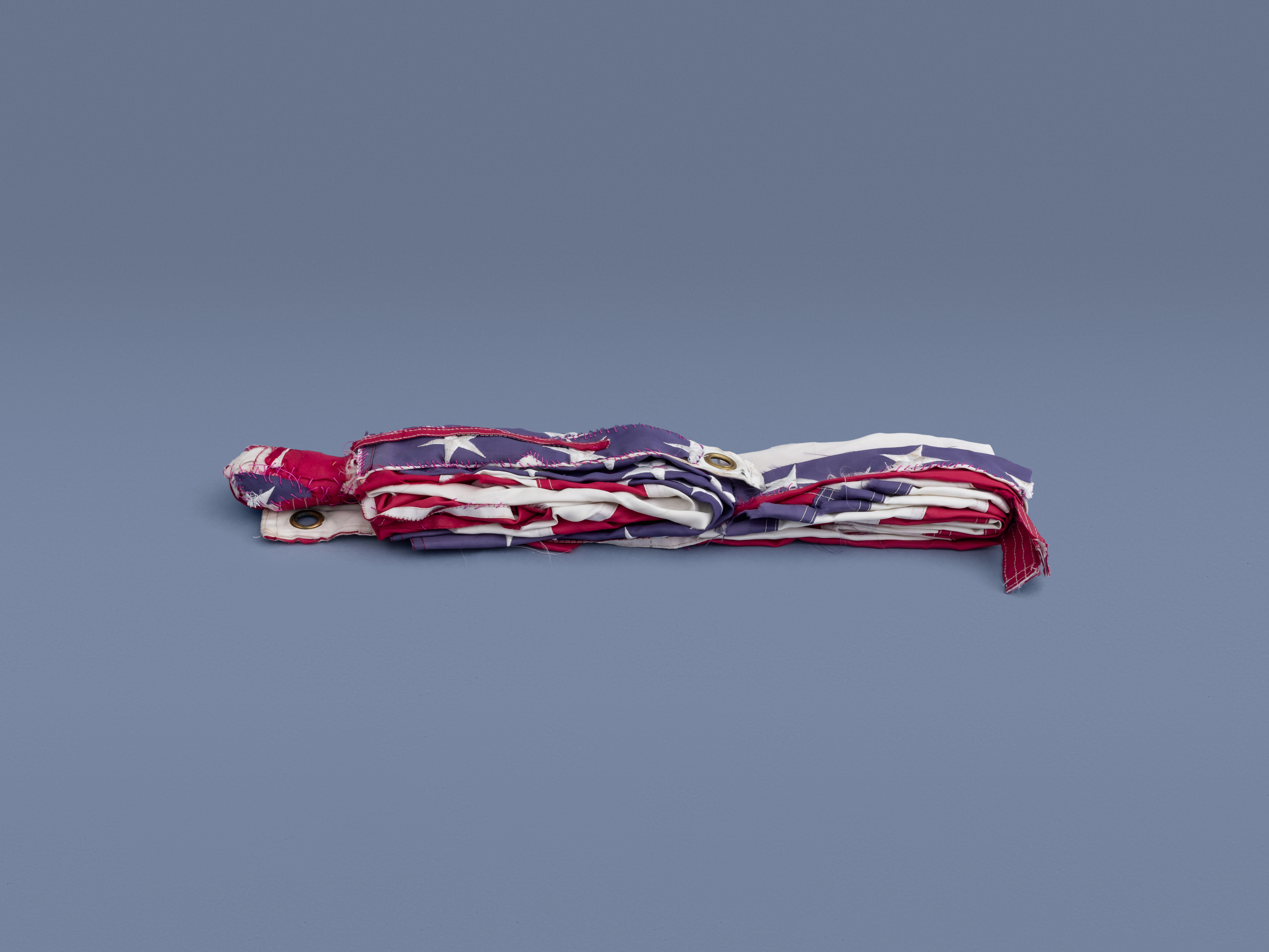

Each of Englander’s statuettes is based on ancient depictions of the Buddha reclining before death, a state known as parinirvana: the ultimate state of peace achieved through self-acceptance, marking entry into Nirvana–a state of pure being. Compositionally, Englander’s parinirvana statuettes fall into three categories. Figures in the first, which draw on Gandharan representations of the Buddha from the second and third centuries, materialise as simple rolls of fabric–the US flag, as in Parinirvana (American flag) (2025), or tartan, Parinirvana (mom’s kilt) (2025). Lying flat on their sides, these skinny Buddhas appear totally dead or asleep, materially accepting the realities of their being. (In Buddhist belief, there is no such thing as a permanent soul or “I”: the self is an ever-changing aggregate with no permanent physicality.)

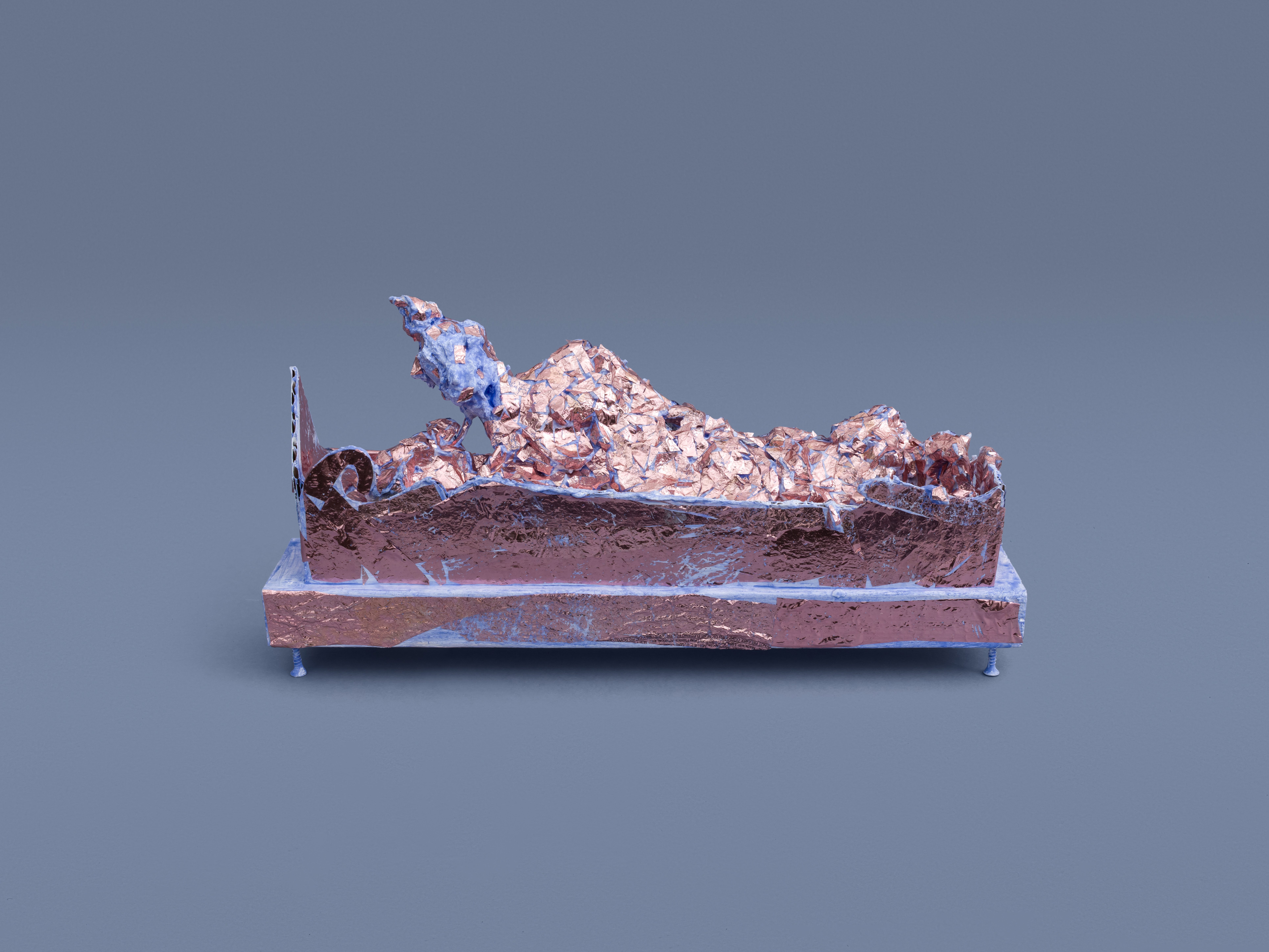

Originally based upon popular South Asian depictions of parinirvana, the second group of figures recalls the porosity of iconography seen in Englander’s promo photo. Propped up on pillows, one hand supporting their heads, these Buddhist-inspired forms rhyme with Henri Matisse’s reclining nudes as well as the sculptures of Henry Moore. Unlike the statuettes in the first cohort, the formal undulations in the bodies of these Buddhas make them feel more alive, albeit in a pained way: wrapped in messy sheets of plaster, their forms are skeletal. As with Englander’s photo, each figure leaves me disquieted, as if each statuette’s physicality is melting away to reveal the delicate melange of their being.

I read this haphazard approach to construction as a nod to the ways in which a sense of self is materially and mentally formed through a “myriad of things”: a strange convergence of sociocultural references and temporal ideologies. The final set of statuettes in The Elizabethan Lumber Room offers the clearest articulation of this idea. The most lively of Englander’s parinirvana, these statutes clash high art prestige with low-brow matter. Parinirvana (UNESCO Betty), for instance, is a maquette-sized replica of Henry Moore’s 1957 sculpture UNESCO Reclining Figure, clad in the rags of the same Betty Boop T-shirt that appears in the exhibition image.

The sculpture is playful, immediately eye-catching, a form that rewards careful observation. Englander has meticulously cut up the T-shirt, using scraps of Boop’s body to redefine the mini-Moore-sculpture’s own. Boop’s eyes sit where the figure’s would be, her hands where its hands would be, and so on. For Englander, this incongruous culture clash “reveals the extent of the distortions in each”; an allusion to how iconic bodies from different cultures fragment and are resewn as societies meet, their meanings shifting in the process.

Reflecting on what is gestured to in the promo image–the vulnerability of being to shifts in sociocultural perception–Englander further aligns her dolly collage with the visuals of “dazzle camouflage,” a First World War painting technique designed not to disguise warships but to confuse an enemy’s weapon systems. By drawing this iconic affinity into her mix of religious and modernist references, the anachronistic nature of Parinirvana (UNESCO Betty) disrupts the social systems that inscribe selfhood and being within a singular, physical body form–something to be objectified.

In an age characterised by the performance of the self, in which we strive to fulfil sociocultural ideals or have them projected onto us, Englander’s work exposes being as a mishmash of shifting cultural references. Her statuettes accept this distortion, inviting us to “remain curious” and to attend to “the many beings past, present, and future with whom a self arises.”

—

Elizabeth Englander (b. 1988, Boston, MA, USA) lives and works in New York. She received her MFA from Hunter College in 2019, and her BFA in Painting from Rhode Island School of Design in 2011. Recent solo exhibitions include Mister Poganynibbana, Theta & From the Desk of Lucy Bull, New York (2025); Eminem Buddhism, Volume 3, The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Ridgefield, CT (2024); Eminem Buddhism Vol 2, House of Gaga, Guadalajara (2023); and Eminem Buddhism, Theta, New York (2022). Englander has participated in group exhibitions at By Art Matters, Hangzhou (2024); Company Gallery, New York (2024); Bel Ami, Los Angeles (2024); White Columns, New York (2023); Lomex, New York (2022); What Pipeline, Detroit (2022); Night Gallery, Los Angeles (2021); and Muzeum Ikon, Warsaw (2018). An essay on her relationship to Buddhist sculpture, Wisdom Kings, was published in 2023 by Theta.

Toby Üpson (b. 1996, Ipswich, UK) is a writer based in Glasgow. In 2025, his first collection of poetry was published by La chaise jaune. He is an Ambassador for Amsterdam Art and a Mentor for What Could Should Curating Do’s education programme. Between 2023 and 2024, Üpson was a Faculty Member of the Metabolic Museum-University based at KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin.