What does ‘punk’ mean today, if anything at all? Once a subcultural movement that started in late 1970s Britain, punk signalled a collective resistance against the monarchy, against economic precarity and against British social hierarchy, with bands like The Sex Pistols and The Clash acting as catalysts for a counter-aesthetic and counter-politics. Punk’s force was its visible performativity and non-conformity to classical ideals of beauty or fashion. Safety pins, tartan, spiked hair, leather and ripped clothing all became synonymous with a movement born of scarcity, rage, DIY culture.

Paris-based artist Christelle Oyiri’s exhibition at Champ Lacombe in King’s Cross (an area marked by derelict housing, redevelopment, and cultural remapping), is a fitting site to explore fractured identity and belonging. Walking into the gallery, the entire two floors are engulfed in floor-to-ceiling red tartan wallpaper, accompanied by a music soundtrack shuffling Sonic Youth, Outkast, Le Tigre, and The Clash. Six grey plastic canteen table sculptures, all titled CHOOSE YOUR FIGHTER (all 2025), are printed on their table tops, each with a separate collage referencing subculture groups: rave, goth, emo, punk, reggae, and skate. The tables are identical to those found in British schools, yet here they are propped upright like temporary barricades, with slogans printed on top of their collaged surfaces: ‘Tears don’t rust’, ‘We are eternal’, ‘Anarchy sold separately’. On a central wall, the word PUNK is printed vertically in large bold black font. The exhibition feels nostalgic, yet, rather than sentimentalising these tropes the works take on a more nuanced position, with Oyiri creating a sculptural tableau to show the complexity of contemporary identity, composed of overlapping fragments rather than allegiance to a single scene.

Subcultures no longer carry the force they once did. The internet enables us to connect with likeminded people without needing a physical community, algorithms reshape taste faster than scenes can be rooted, and the commercialisation of “rebellion” has turned dissent into a purchasable aesthetic. Subcultures haven’t faded because people no longer want to belong to something, but because the structural conditions that once made them politically charged and collectively organised have dissolved. Culture has become intensely aestheticised, and styles now shift far more quickly than the ideologies that once anchored them. Punk, goth, and rave, (all movements rooted in communal and political struggle) now exist mostly as a visual aesthetic. In this landscape, identity becomes fluid because firm boundaries and coherent subcultural homes have disappeared. Today, the question is less “What group do you belong to?” and more “Which aesthetic languages are you borrowing, combining, or navigating, and why?”

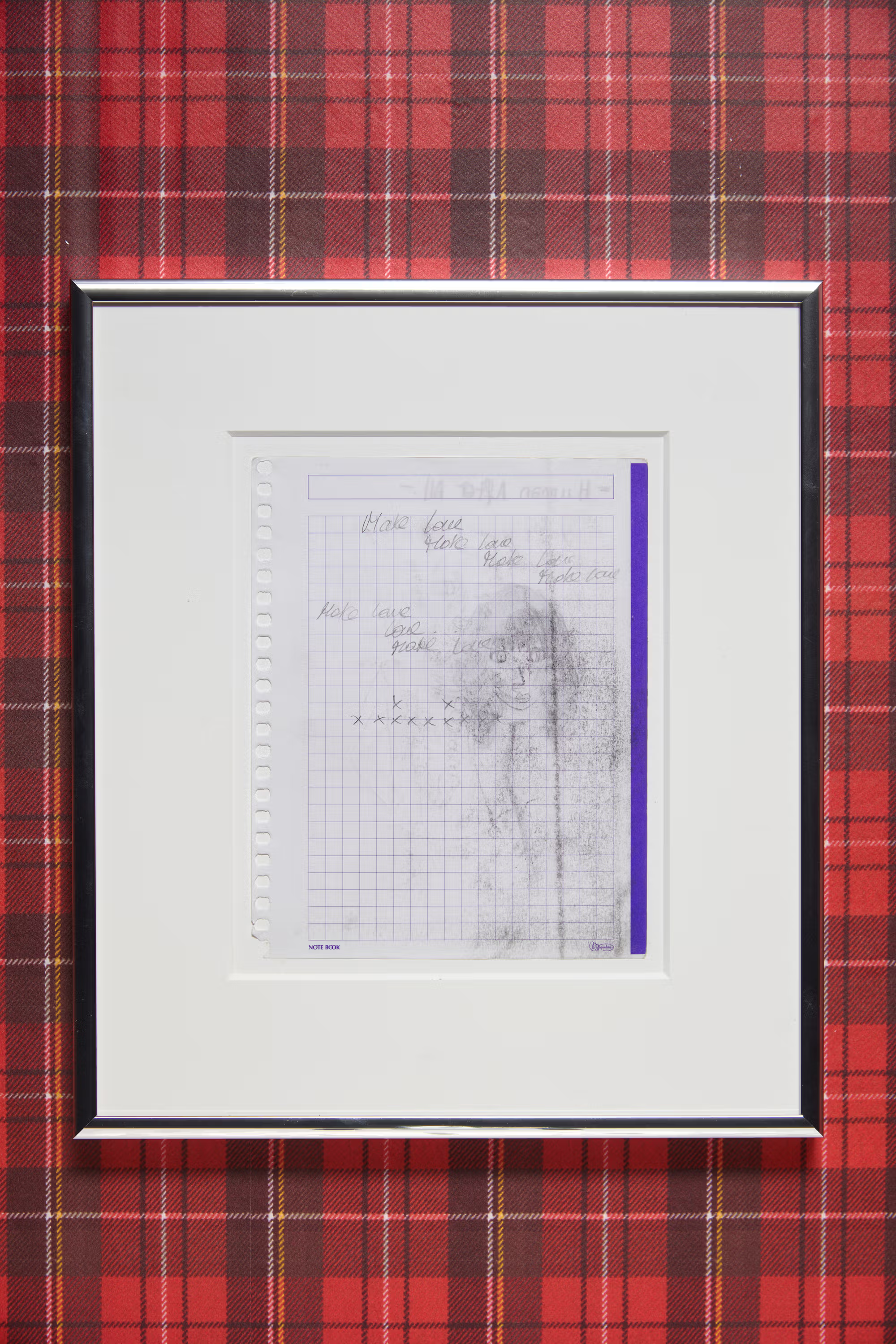

Downstairs, a white canvas emblazoned with the word POSER in gold-plated letters is an incisive provocation. In an era of social media, we are all, in some sense, posing and assembling selves from repurposed signs and symbols, negotiating visibility within algorithmic economies that reward a certain type of aesthetic. Nearby, a series of collages titled Diary of an Insufferable Teen are made from school notebooks, collaged with scribbled drawings, concert tickets, and adolescent detritus. Their tenderness is disarming. These are the material residues of a young person yearning for belonging, unsure which subcultural code to inhabit, reaching toward somewhere beyond their immediate circumstances.

Oyiri’s practice broadly encompasses music, moving image, drawing, installation and performance. Her installations operate as speculative cartographies of identity and power, mapping how displacement, diaspora, and erasure shape the cultural imagination. In this exhibition, she uses the languages of subculture not to nostalgically revive them but to examine their legacy, and to question what remains when the original conditions of subcultural formation have nearly dissolved due to the internet and alternative ways of gathering.

Her work is not nostalgic, rather it is diagnostic, confronting the political and psychological consequences of living in a post-subcultural age: an era in which subcultural tropes have been aestheticised, and identity endlessly editable. And yet, the entire exhibition is a reminder that while subcultures may no longer exist as fixed entities, the impulses that generated them are still alive, searching for new forms. Perhaps that, ultimately, is Oyiri’s most compelling claim: punk isn’t dead; it’s been dispersed, and its politics survive not in a singular style or scene but in the ongoing struggle to build meaning within systems designed to demolish it.

—

Artist, producer, and DJ (under the pseudonym CRYSTALLMESS), Christelle Oyiri (b.1992) works across multiple disciplines – from music, film to performance and installation. Oyiri has described her work as focusing on ‘the things that lie between the lines’, including lost mythologies, subcultures, and diasporic histories. This exhibition focuses specifically on those subcultures. An unspoken visual lexicon - be it punk, goth, rave, emo, hip-hop, subcultures defy the normative and masquerade against the grain with each of them possessing a distinct visual lexicon, fostering and building a sense of community over.

Sofia Hallström is a writer based in London.