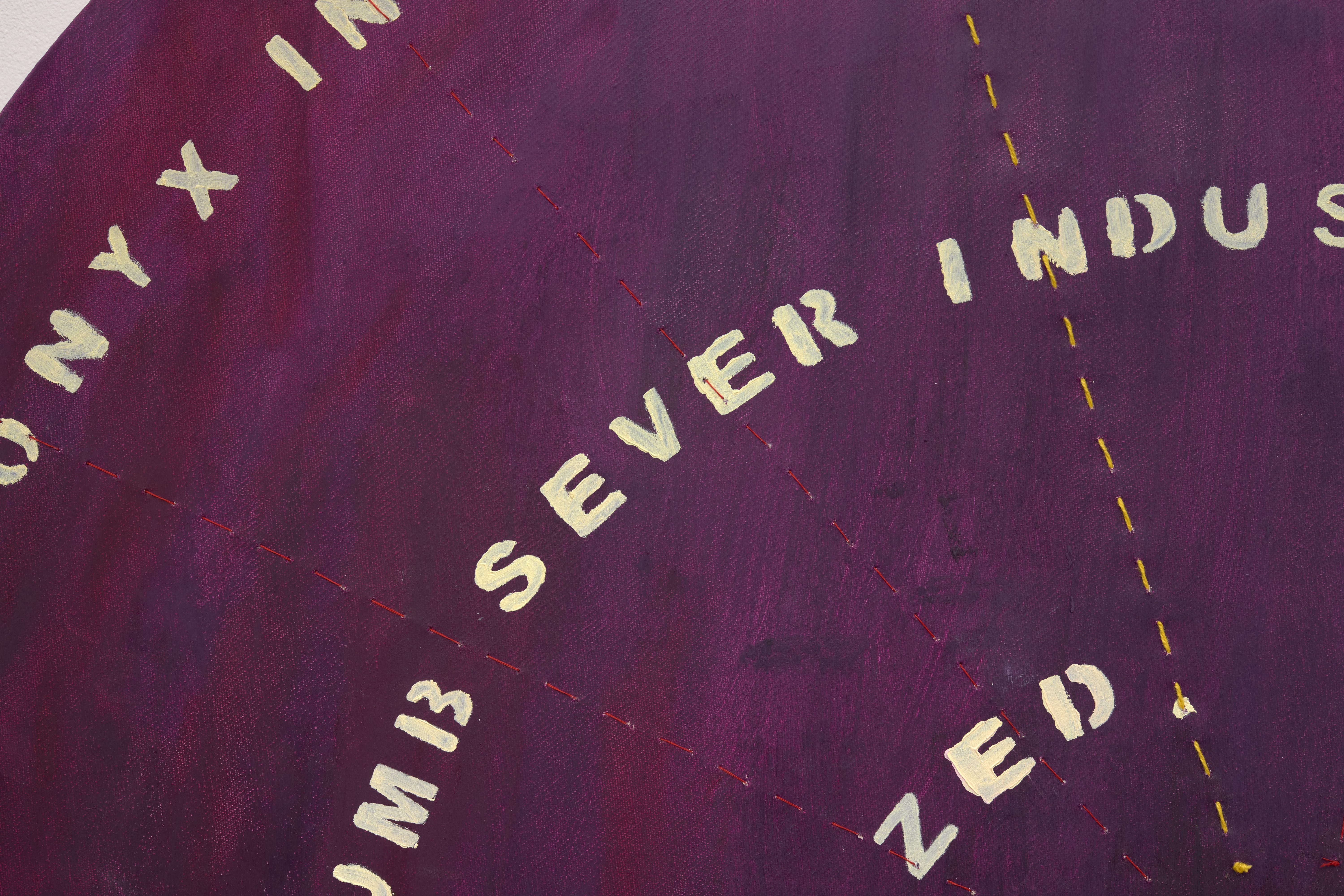

HUSH MR GIANT – Hannah Black’s first solo presentation in the UK since 2020 – is a show about how the mighty fall. Displayed at Arcadia Missa in London, the exhibition consists of six circular oil on canvas paintings, reminiscent of the surrealist, spinning discs and hypnotic wordplay in Marcel Duchamp’s 1926 film Anemic Cinema. Drawing on this traditional style of optical art known to avant-garde painters, Black’s work features text from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), contorted into nonsense poetry. Black’s anagrams produce random meanings that complicate, pervert, and problematise both the Western concept of universality – the notion that only empire can defend human rights globally – and its embodiment in language.

Black illuminates the inherent contradictions and distortions in colonial logic, themes which have been urgently brought to the fore by the genocide in Gaza, and Britain’s active participation in those crimes. The tension between suppression and resistance is a constant presence throughout her work: lines stitched into the paintings by a needle and thread delineate the astrological charts of historical uprisings, including the Haitian and French revolutions.

Each painting is titled with the original text from the Declaration. One piece bears the inscription “No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment (Algerian revolution)”, which Black reconfigures into the line: “Now ensured be hell in sleeve arroyo surface chewed his livery on the slate…”. Similarly, another is titled “Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference (American Revolution)”, and has been translated as: “If re-won haze deride two three doms are pinioned in neck’s…”. These haunting yet satirical manipulations of language not only evoke the collapse of meaning under empire but also point to the emergence of new possibilities – new ways of reading and inhabiting the world in the wake of such ruin. In HUSH MR GIANT, the language of empire is no longer fixed or immutable; it is unstable and in perpetual flux.

Black’s wordplay recalls the cut-up technique of William S. Burroughs, who argued that slicing and randomly reassembling text can expose hidden potential in language: “when you cut into the present”, he suggested, “the future leaks out.” If Black gestures toward a future – a new wor(l)d order – then it is one where the immersive fantasies of Western society are laid bare. The notion of a just or necessary colonial power is no less than a hypnotic distraction, the artwork points out, that continues to keep us in a trance while global inequality and dehuminisation persists. Black’s seductive designs attempt to expose how this form of fiction, though absurd, acts like a spell.

Another way the artist brings our attention to the deception of empire is by highlighting its inconsistent definition of universalism. This tension feels most overt in the paintings entitled “Everyone has the right to leave any country, including his own, and to return to this country (Great Palestinian Rebellion)”. This is another grimly ironic pronouncement that has been satirised by Black so that it becomes: “If ruin has tired to live on ache and thee ink loading his urn and torrent…”. Framing the history of Palestine in contrast to the Declaration's supposedly universal concept of return, Black uses highly literal methods to bring Western hypocrisy into sharp focus – its destruction of the Middle East disguised as humanitarianism – and how this contemporary violence is part of Britain’s past.

This work, and the exhibition in general, is also more than a statement about the duplicity of colonialism. It serves as an invitation to reflect, more specifically, on the conditional nature of human rights; in this case, “the right to return”, which Palestinians have been denied. Black’s stark juxtapositions bring to mind the assertions of anti-colonial scholars who have observed how the protections provided by the West, which are ostensibly designed to be shared by everyone, are in fact constantly redefined, reinvented, and shaped by movements of power. Jacques Derrida, for instance, describes citizenship as an “artifice” – something that can, at one moment, be perceived by nation-states as an innate right and, at another, taken away.

Black’s paintings readily expose this artifice: safety, freedom, independence, protection, and other promises made by the West as part of its ‘civilising’ mission appear to us as mysterious, illusory spirals. At first glance, HUSH MR GIANT might mesmerise and enchant, but to seriously engage with the work is to be awakened, as if by an urgent jolt, into a new state of consciousness.

—

Hannah Black (1981, Manchester) lives and works between London and New York. Black’s work functions conceptually through a co-dependence between thinking and feeling, using conversations and collaborations featuring texts, voices, prints, videos, sculptural interventions, and performances. Her work has been presented in solo exhibitions, including at Fitzpatrick Gallery, Paris; The Art Gallery of York University, Toronto; Luma Westbau, Zürich; Arcadia Missa, London; Kunstverein Braunschweig; Performance Space, New York. Black’s critical writing encompasses various contributions to The New Inquiry, Artforum, and Bookforum. Her previous books include Tuesday or September or The End (2021), Dark Pool Party (2016), and Life (2017, with Juliana Huxtable).

Alexandra Diamond-Rivlin is a writer focusing on queer themes in music, literature, visual culture, and politics. Her work has been published by The Guardian, The Observer, Frieze, The London Standard, Dazed, AnOther, Teen Vogue, Glamour, and more.