There is a phenomenon in which indistinguishable fuzzy audio morphs to the sound of certain phrases as they are read and thought of. Read one phrase, and the audio sounds like it, change and read another phrase, and the audio changes to sound like that, too. Lutz Bacher is invariably ‘eclectic’, ‘elusive’, ‘enigmatic’, ‘difficult’, yet the growing criticism around her tends to be just the opposite, very sure of its words. Burning the Days side-eyes the standard obligation of a posthumous survey to join up imaginary dots with wall texts and chronologies, giving difficult work easy language in an attempt to outrun the noise which, nevertheless, slips its way back into the world of objects. This show, like Bacher, gives in to noise.

Two compact metal cases bear the sticker label ‘Snow White.’ I think they contain costumes for a stage adaptation, though later learn they hold film reel for the Disney movie. Rip off the sticker and the object still has something to do with Snow White, it cannot be reduced to a language exercise precisely as the case and what it purports to contain are not cleanly separable into ‘thing' and ‘idea,’ there’s too much spill for cold conceptualism. It’s a quiet and appropriately unsteady intro to the show, and to Bacher, an artist adept at both placing objects at ironic remove, and letting them run off with secrets beyond her–or anyone’s–exercise in irony.

A room of stress balls scattered on the ground hint at witticisms. They are bereft of use, dumb hindrances out of reach. Populating the gallery walls, framed pages taken from an old astronomical guide: small black and white images of stars and galaxies on ageing brown pages, number paginated, with captions underneath of technical detail not all that enthralling. Paired with little stress balls on the floor, it’s a downsizing of celestial awe. It’s also more than this conceptual rugpull. One caption reads ‘each of these objects is an entire “star city,” containing several hundred billion suns. These are the major units of creation.’ The words slide to metaphor, registers not just of information, but of an authorial voice, a poet, a gnostic mutter. Bacher has an eye for irony, yes, but also for what cannot be conceptually contained, making fun and making miraculous both together.

Conceptualism is a word that hovers around Bacher. Upstairs there’s even a facsimile of Marcel Duchamp’s Bicycle Wheel, albeit painted white like Ikea furniture. The show is made up of many such ‘readymades,’ though Duchamp is left spinning. On the first floor, objects are displayed with a thrift-store-find logic. A bowling ball sphere printed blurred green and blue, like a blown-up, botched up map of the Earth. A gingerbread man-like figure of polished wood leans against a wall, angled into a seat by unwieldy hinges. Too big to be a sensible toy, too small and undynamic for human verisimilitude. Not particularly functional as a seat.

Readymades that do away with origins, and do away with authorial ideas and thoughts too. This is no tidy conceptualism like Joseph Kosuth’s One and Three Chairs, it cannot be reduced to language, a set of ideas or questions. Bacher is not narcissistic enough to think the thoughts she projects onto her objects are more interesting than the objects themselves, or than what others might think of them. She makes miraculous choices precisely as she is willing to lose control, picking out things saturated beyond a singular solipsistic use or artistic vision. Fingerprints, stressmarks. Wear and tear. Mass produced labels, illegible handwriting. Messages by unknown people. Clothing sizes, stains, industrial manufacturing errors. Postal addresses, trace on trace.

Downstairs, a series of framed images of a huddle of sunlit soldiers in their downtime, topless, towelled, smiling an unsure smile. The kind of smile you might reply to an emphatically warm greeting from an approaching person you can’t quite recognise. Part reciprocal, part preemptive guard. The sequence of frames is ambiguously ordered so that it is difficult to place whether it is a series of crops and selects of a single photograph, or of panned and zoomed stills from a moving image. It’s like dragging a cursor across a video timeline, searching for something in each frame: a sudden gunshot, an ambush, a drop of the towel, a hushed glance between two men, desire. Unable to timestamp the right moment. Motion must be going on elsewhere, in secret.

Upstairs by the museum terrace, a small monitor shows A Girl in a Blue Dress, a video shot on a handheld camera zoomed in so heavily that each movement of the hand appears in blocks of leap-like motion. Focus moves from the girl’s midriff to chunks of her surroundings, the Musée Picasso. A man, identifiable by his clothes, stands beside her from time to time, perhaps accompanying. It might just be coincidence. To assume she is being followed feels like a morbid projection; to assume she is of no interest at all feels like a refusal to look closely enough. The video evades narrative, yet its affective charge makes looking the other way a decision to miss something ineffably important.

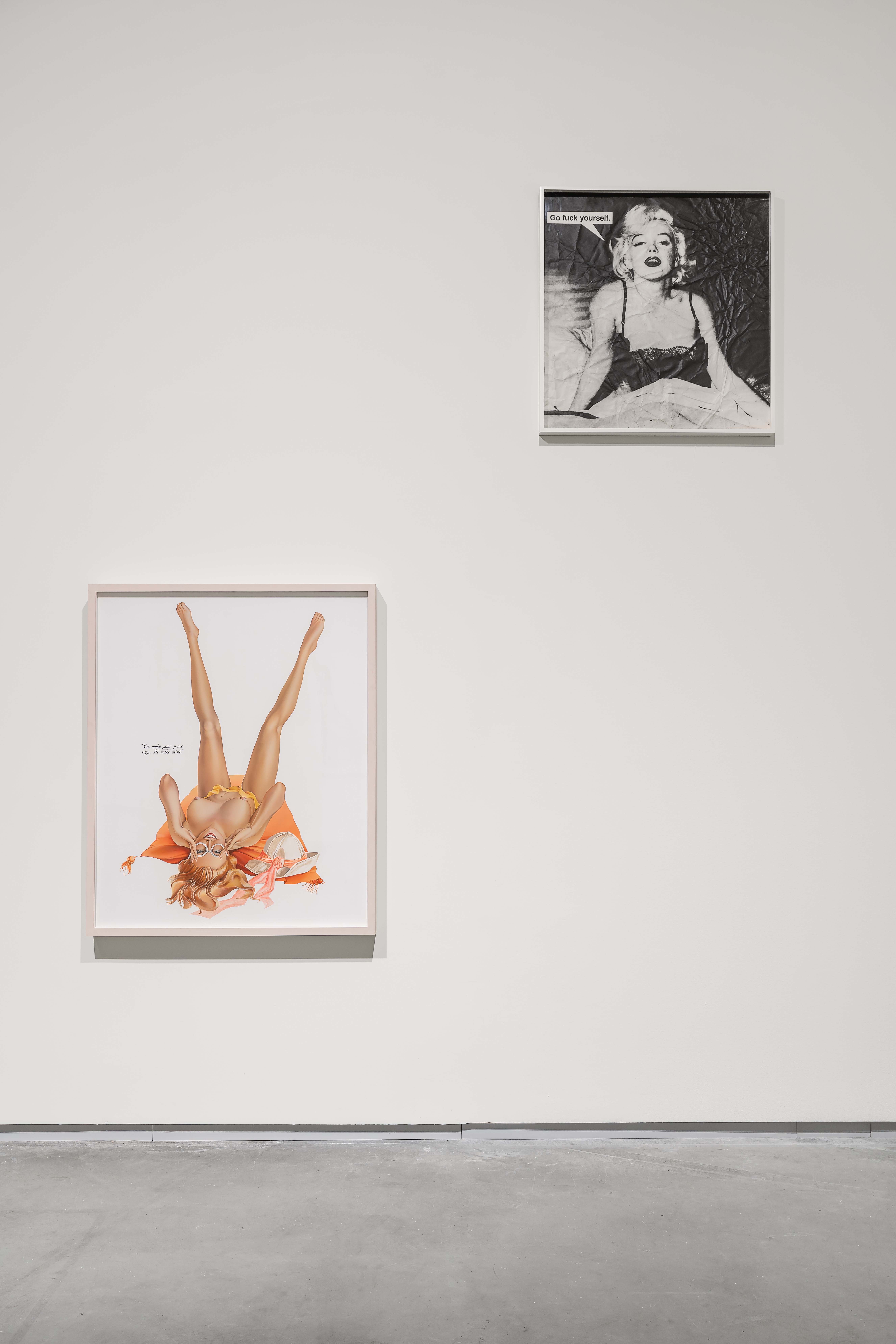

Much of the show is gender-loaded, but it’s no dualistic gun duel. Downstairs a series of media shots show Jackie Onassis slipping away from unwanted attention. Under one photo the caption reads ‘the most desirable woman in the world wanted to be chased by me, Ron Galella, the paparazzo. I knew even then that there could be no stopping, no turning back.’ Upstairs a polished slick painting of a Playboy illustration, a huge-breasted blonde cartoonish woman, thighs folded just enough, and a tagline ‘Sure I’m for the feminist movement / In fact, I’m pretty good at it.’ Men look at women. Men also look at other men looking at women, stealing ideas of their own sex from each other like poker chips. Exercises in male desire happen in covert deals, imbalances, wins and losses between men and men, not just men and women. To strange results.

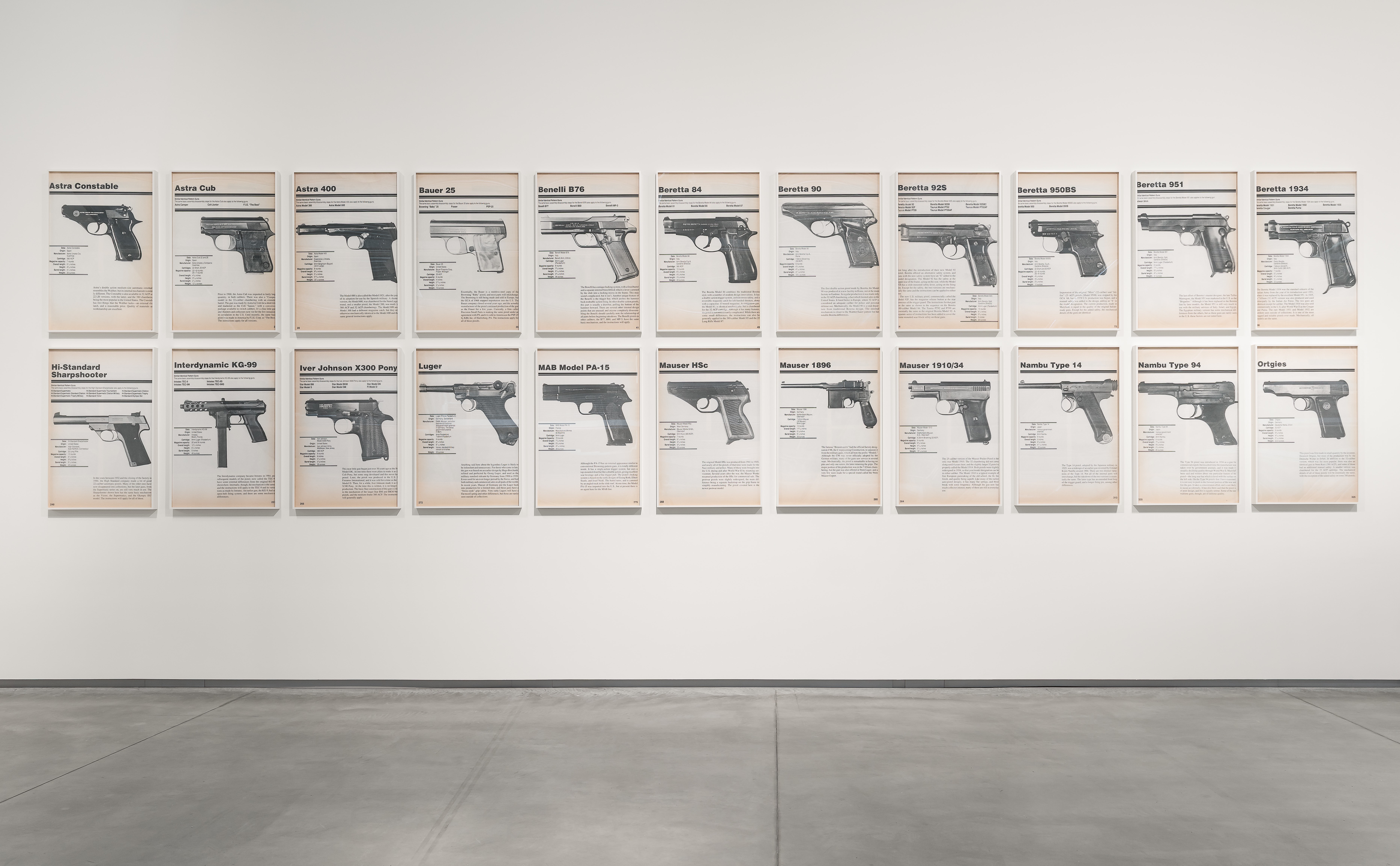

Power mechanisms move inscrutably. FIREARMS consists of framed prints of individual gun models taken from an instruction manual. CZ 27. CZ 45. Smith & Wesson 459. Galesi 25. Together the select pages index technicals, specs, genealogies, skimming names across a history of twentieth century violence in sideway glances, waterboatman-like. Downstairs, press clippings and facsimiles of handwritten preponderances on JFK’s assassination. One gunshot, two gunshots, three. The grassy knoll. A second gunman. Harvey Oswald as stand-in. One line of interpretation splinters into conspiratorial bloom, the case stays open.

Bacher doesn’t do artistic gestures or plan idea puns, her work glitters in surfaces and surfeits of meaning, not just its depletion. So often cast as runaway, renegade, enigma, it might do well to heed her own warning gaze toward paparazzo Ron Galella. Others do more than just reflect our own intentions and desires. Onassis, like Bacher, might not be running away from anything or anyone, might just be looking out, with sympathy and empathy, into the world.

Something Burning the Days does well is embrace Bacher’s scatter-gaze outward, to correspondences, dislocations, standalones. A Girl in a Blue Dress brrrs on an inconspicuous monitor up some steps, next to a staff-only door. The sounds of Sweet Jesus, an audio recitation from the book of Matthew, booms from speakers on the museum roof terrace, floating across the canal to the wall-to-ceiling office windows opposite. I am in Oslo. I am put up in a hotel called The Thief for one night. The Thief is on ‘thief islet’ (Tjuvholmen), so called as a former ‘haunt for dubious characters and thieves.’ The hotel website reads ‘the city district which was once home to criminals and shady dealings is now a power centre for contemporary art and good city living at the water’s edge.’

I do not know whether the speakers for Sweet Jesus are turned off when the museum closes, or left on into the night, or whether the office workers hear anything behind their glass.

—

Lutz Bacher was an American artist, born in 1943, who lived and worked in Berkeley and later New York, where she died in 2019. Lutz Bacher was, and still is, a pseudonym.

Phil Tarrant is a writer based in the UK.

.jpg)